Menu

|

After 15 seconds into Murur al-Kiram, Kinematik’s new album to be released on February 28, you already know that you are in for something exceptional. There is no way that an album can start with such a strong drum beat and then end up being a weak recording. Starting an album on a drum beat only also means one thing: Kinematik have thought about this album carefully; they know what they are doing and nothing is random. Murur al-Kiram is a real album, not a collection of songs that were “just ready” to be released. Kinematik may not know it, and they may not even care about it, but their album exactly follows the playbook of “how to approach album track order in the digital age”: start strong - tell a story - don’t worry about shuffling. “What is the story of Murur al-Kiram?,” I ask Kinematik when I meet them in Beirut at the beginning of 2020. Anthony Sahyoun, Rudy Ghafari and Akram Hajj all sip beers when talking to me in the basement of Riwaq, one of their usual hangout places. Anthony is the most outspoken member of the band, so he goes first, as often. “Our first album was a compilation of everything that we were able to do at that time,” he says. “The artistic decisions only had to do with our capabilities as musicians. It was like, ok, this is what we can express, this is what we know how to express, so let’s put it on record.” Rudy Ghafari adds his version of how the second album is different from the first one: “You can say that the first album was one big happy accident. Whereas the second album is a series of mini accidents.” Murur al-Kiram is indeed very different from Ala’, Kinematik’s first album. It contains less guitars and more synthesizers and is driven throughout the album by the multifaceted double drumming of Akram Hajj and Teddy Tawil (who is not an official member of Kinematik, but collaborates with Anthony on another exciting project, May Bardé). If I had to come up with an abstract of the underlying story of Murur al-Kiram, it would go like this: Murur al-Kiram starts with an optimistic, powerful beat which could be a metaphor for young boys enjoying a happy youth somewhere in the fresh air of the Lebanese mountains. Soon the drum beats are followed by synthesizer sounds, the musical expression of fantasy landscapes and future universes of which an innocent adolescent in Lebanon can only dream. "Our presence here is like Murur al-Kiram, like en passant. We are here, but they don't care." With “W Kaza”, the ninth song of the album, the Lebanese reality brutally kicks in. The song is pure destruction and exhaustion, like banging your fists in protest against the gate of a palace (or the building of a corrupt government, if we want to stay in the Lebanese context) that will remain closed, however strong you bang. Murur al-Kiram ends with “Roza” - the most “churchy” of our new songs, as Anthony explains - because after all, when everything in Lebanon is said and gone, religion will stay to soothe the ones that have not found their worldly redemption yet. Since October 17, 2019, the Lebanese again try to change their political system and in fact the entire society, having come out in masses to the squares and streets to protest against the ruling class, the corruption and the sectarian system that suffocates the country and its people. The album's title Murur al-Kiram, which can be freely translated as “the privileged are passing by”, is a sarcastic reference to how Kinematik feel about their situation as Lebanese citizens (and this even before the thawra, as the album was recorded prior to October 2019). Like many other Lebanese, the members of Kinematik sense that their presence in the country is not validated in any way. “It’s like a what-the-fuck-am-I-doing-here kind of thing,” says Anthony. “Our vote, our life has no value. We are stuck with the status quo, our presence here is like Murur al-Kiram, like en passant. We are here, but they don’t care.” “When you listen to W Kaza,” says Rudy, “then remember all your visits to Beirut. That’s the track that expresses most how we feel about everything.” Anthony agrees. “Track nine is literal exhaustion, that’s what it is. It’s exhaustion and defeat and it comes from the drumming. In this song we have this really heavy drum sound and this really heavy bass line. In the studio Akram was slowing down because he got exhausted playing it. And your impulse as a musician would be to pick up the tempo again. But we said no, don’t pick it up. Just get exhausted and let it slow down all the way.” Slow down until all your black thoughts have vanished. What happened to Lebanese band Mashrou’ Leila last year was a big shock for Kinematik. (Mashrou’ Leila were banned from playing at the Byblos festival in Lebanon in 2019. They became the victims of a political power game that was played out on the band’s back, with people leading an online campaign against them because of one or two lines within their lyrics that made references to religion. Of course the fact that Mashrou’ Leila’s lead singer is gay didn’t help their cause either.) “When we last met,” I tell the band, “we talked about your black thoughts. Your ideas about a lot of things are blacker than Mashrou’ Leila’s, but people don’t realize it because your songs have no words.” “Actually my mother said this to me when the Mashrou’ Leila thing happened,” Rudy says. “I was arguing with my mother. She told me, Rudy, your music is actually worse (than Mashrou’ Leila). When Mashrou’ Leila use a reference from the bible, people go crazy. Put words to your music and people would be very pissed off. It’s way worse.” So far Kinematik haven’t put words to their music, because it never felt organic and natural. “If we did,” says Akram, “I think that I would like to say something very melancholic and sad.” “True. there is sadness in our music,” Rudy comments. “But actually, and put the music aside, we are happy people. Despite the depressions we go through. And despite the anger.” Yes, the general tone of Murur al-Kiram is melancholic, however the album is not as gloomy as it might seem when reading these lines. There is also much beauty and hope in Kinematik's music. At the end of the day, Anthony, Rudy and Akram want to stay in Lebanon, they don't intend to leave the country as many Lebanese do. When Lebanese sound defeatist in their talk, it's often meant to be funny, not depressing. To make an album great, it’s not only the music that counts, but also the pauses and the transitions between the different parts of the recording. Judging by this, Kinematik have done an outstanding job with Murur al-Kiram. As Anthony keeps repeating during the interview: the band tried to be as honest and as hard on themselves as they possibly could when recording the album. The material was reworked and reworked until it felt right. There weren’t any hacks and cheap tricks allowed this time around. The composing of Murur al-Kiram was like “you have an idea, you try to abuse the idea,” Anthony explains. “And if the idea survives all of your abuses, then it was a good idea and you keep it.” The result is Murur al-Kiram. It is an album full of ideas that have survived. It is an album made by people who have survived. It is an album that won’t just pass by unnoticed. photos and cover art by Joe Saade

1 Comment

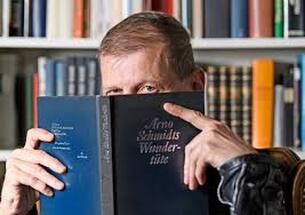

His numbers on Spotify are very modest. When I talk to Andrea Kaiser, who is just Kaiser to most people, I tell him that he has ten monthly listeners on Spotify (and one of them is me). That’s awesome, Kaiser replies, I’d love to send everyone of them a bouquet of flowers. Catering to the masses has never been Kaiser’s goal when making music. In fact he would change his musical style immediately should this style ever become mainstream and enjoy commercial success. In October of 2019, one month after the release of his latest album Songs of No Return, this is not a particular risk. Kaiser is the founder and at present the only member of Dnepr, a band that started its career deep down in Bern’s underground music scene of the 1980ies and has not moved up considerably since then. (And yes, there used to be an underground scene in Switzerland.) Do you still talk about the 1980ies?, I ask Kaiser. Sure, he says, when I’m asked. Kaiser’s memories of the starting years of his career are still very much vivid. Between 1987 and 1995 he had released a bunch of six records and he still remembers every detail about each of these songs. Dnepr combined Kaiser’s heavy guitar - sometimes rhythmic, sometimes gloomy and plaintive - with elements from post punk, prog rock and new wave. The intention was always to be provocative, with a distinct nihilistic attitude, and play with political buzzwords in a period when the cold war was still fully on. Dnepr is a great motorbike brand from Ukraine, Kaiser tells me, and I wanted a name for my band with an eastern, communist touch. Dnepr’s first album was called Hymn of Nihilon and it was inspired by Alan Sillitoe’s novel “Travels in Nihilon” where a group of people is sent to the country of Nihilon to collect information for a new travel guide. In Nihilon honesty is outlawed, drunk driving is mandatory and nihilism reigns supreme. TV and radio news are announced with “Here are the lies!”. These are just the kind of subversive ideas that Kaiser loves. All of Dnepr’s albums were recorded in Nihilitz Studios at Ulaanbaatar; Nihilitz being the drink that Nihilon’s citizens usually drink and Ulaanbaatar the capital of Mongolia, a former hidden treasure of a communist-ruled country. In reality Kaiser’s studio is just a small room in the basement of his apartment in Bern, just big enough for him and his guitar. Kaiser has never traveled to Ulaanbaatar. While Dnepr’s music is purely instrumental now, there were lyrics in the first period of Dnepr. Have you lost your inspiration for words?, I ask Kaiser. Not at all, he replies, I never had troubles expressing myself. It’s just that I find it more challenging these days, but also more of a thrill, to produce music without lyrics. With lyrics, you can repeat them over and over again and you have a song. Without lyrics, your compositions need to be constructed differently in order to keep the song going and the audience listening. Dnepr has always been avant-garde. For “Figures in a Landscape” from Hellhome, Dnepr’s 1993 release, a computer generated voice spoke words that had been fed to the computer by Kaiser (by profession, Kaiser is a software engineer). “Deus Ex Machina” and “The Nile Song” (both from Vandalism, 1991) are similar adventures in sound. Other songs on Vandalism - “The definitive Birth, the ultimate Life and the absolute Death”, as well as “Come back (I want to kick into your ass)”- definitely excel through their innovative titles, one profound and one more than subtly funny. By comparison, The Empire Strikes Back from 1990 is a rather conventional album, with music that can be qualified as industrial heavy metal based on piercing guitar riffs. What did stop you from becoming as big as Metallica?, I ask Kaiser, because you certainly had the talent. Well, I don’t know, says Kaiser, always the humble man. It also has to do with luck. You need to be young to start such a career, to make it big. Music consumers today are kids and teenagers. They need to be able to identify with you. If you are 30 plus, that’s almost impossible. Add to this Kaiser’s eternal refusal to compromise on his music and you know why Dnepr is not a household name in the charts. Fast forward 23 years to the beginning of 2018. The world has not heard a lot from Dnepr, or Kaiser, since 1995, certainly not in the form of an album. What happened, Kaiser? Kaiser doesn’t want to talk about these years of near retirement, except in private mode. But then, slowly slowly, he crawled back to life and music and reactivated Nihilitz Studios. Songs of No Return is promoted as your comeback album, I mention to Kaiser, but actually you have already released The Nine Gates two years ago. I am happy that you make me talk about it, he replies, so for the first time I get to explain what is the story behind the nine gates. "Maybe I am infected by a software virus that damages my operating system." The first connotation with this album title are the nine gates that lead to hell, Kaiser illuminates me. But I also see this as the nine month of pregnancy and thus you arrive at an equation life = hell. Most people find life quite ok, because they have a mechanism built in that helps them to suppress any fear or doubt they may have. Without this mechanism, we couldn’t exist. For myself, this mechanism is slowly wearing off, maybe because I am infected by a software virus that damages my operating system. George Orwell helped me to see that I am not alone in this: “any life when viewed from the inside is simply a series of defeats”. How come The Nine Gates has twelve tracks? The three extra tracks are the afterbirth. It happens quite often. I have a concept, I write tracks, and when I’m done, more stuff needs to get out. With Song of No Return, Dnepr and Kaiser are really back. The album consists of twelve songs that Kaiser wrote and recorded all by himself. I am inspired to work alone at the moment, says Kaiser, it’s efficient, no discussions, you don’t have to convince anyone. Would you consider yourself a loner, a bit of an oddball?, I challenge Kaiser. Yes, he says, to a certain extent. However I am not antisocial. The Open Enso Talks: one hour with Kaiser a/k/a Dnepr (language: Swiss German) The new Dnepr album is literature turned into music. Kaiser likes to read - long, difficult reads, mostly from dead authors - and he knows his books well. “Zettels Traum” is inspired by the monumental work of the same title by Arno Schmidt (my song is not a musical abstract of the book; it’s the soundtrack of a dream with breaks and surprising twists, Kaiser says); “Venaska” is a main character in Alfred Döblin’s utopian novel “Berge, Meere und Giganten”, polygamous and bisexual (the book is about contrasts. It’s a dystopia with a woman, a goddess of love, who is called Venaska. I tried to compose a song that is oscillating between the ugly and the beautiful).

Kaiser is a nerd for sound. At any time of the day he may feel inspired to go down to the basement, in his studio, and work on a track. All night long, if needed. Once he dreamt of a counterpart to a leitmotiv he had composed earlier. When he woke up, he immediately ran downstairs, naked as he was, strapped on his guitar and recorded the idea. Are you nerdy with guitars as well?, I ask Kaiser. I am not a collector, he says, I only own two guitars (two handmade Gordon Smith guitars, made in UK). In the end it’s the effect pedals and the amplifiers that create the sound. If I go to a concert and the guitarist hauls a rack with five guitars onto the stage, I know that I am in the wrong place. Dnepr have never played a lot of concerts, not even in their primetime in the 1980ies and 1990ies. In 2018 Kaiser played one set in the knight’s hall of an old castle near Bern. This year, there were the album launch in September and another gig in November. And that’s it. I like to play loud, Kaiser explains, really loud. Preferably at 120 decibels. In most places that’s not possible. But I can’t trim down. Playing my music at 93 decibels? Even whistling is louder! Already Kaiser has ideas for a next album. Is he recording? Not yet, he says. I am all about re-inventing myself. But when I start something new, I find my old music crappy. I am not yet ready to ditch Songs of No Return. That’s why I stick with it for the time being. I don’t even remember how I came up with the last question for Kaiser, but I must have been touched by something when listening to Dnepr’s albums: does he believe in love? Despite of his wary attitude towards society and his reluctance to comply with the masses, despite of all the utopian landscapes and the dystopian soundscapes that he creates: everything in Kaiser’s music is love. It’s a love that he gives and a love that he yearns to receive, forever carried and supported by the big waves of hope - hope for humankind, hope for a more human society - emanating from the strings of his guitar in Nihilitz Studios at Ulaanbaatar. It is because of love why we are on this planet, Kaiser answers. Without love we wouldn’t do anything, without love we wouldn’t make music. We would simply squat on the ground and pick our noses. Dnepr will perform at Les Amis/Wohnzimmer in Bern, Switzerland, on November 14, 2019. Be there (and have your earplugs handy)! My good friend Georgy Flouty was very excited. “You’ve got to listen to this,” he whatsapped me in August. “It’s the best album I’ve heard in the last five years, a French trio in their early twenties.” Georgy is not just anybody. He is a very talented musician who plays the guitar in a number of Lebanese bands, among them KOZO and Sandmoon. I immediately kicked off Spotify. “I like what I hear, very much so,” I replied to Georgy soon afterwards. “And you know what? They will play in Zurich on October 9. However there will be Deafhaven the same evening.” “They are insane live,” Georgy texted back (although he had never seen Lysistrata in concert, only some YouTube videos), “It reminds me of the first time I heard Spiderland (Slint’s legendary post-rock album). The same rush of heavy emotions.” And then: “Deafhaven can wait!” It’s October 9, I am in Zurich heading for Dynamo, a small club near the Limmat river. Lysistrata will perform here this evening, opening for Decibelles, a French band as well. Originally Lysistrata were scheduled to play at another venue, but the concert was canceled because of low pre-sales. Luckily Lysistrata were able to convince Decibelles to take them onboard for their gig. There is a lot of competition in town tonight. Lysistrata are a household name in France but even the best bands have troubles finding their audience if no one knows them, like in Zurich. In a few days, Lysistrata's second album “Breathe In/Out” will be released. Meeting the band proves simple. Ben (drums), Théo (guitar) and Max (bass) are very accessible and easygoing. We sit down on the edge of the stage and start talking. Max is holding my mobile phone like a microphone to better record his and his colleagues voices. “How did you approach writing and recording a follow-up album when your first album was so successful?,” I ask the band. “You can only disappoint.” Ben is the first to answer. “We didn’t ask ourselves too many questions. We had all these riffs and stuff so we kind of assembled them. Our first album was a bunch of songs we had played for a long time and we wanted to get them on a record. For the second album, we were getting tired of playing the same songs all the time. We needed to produce some new stuff.” “Artistically we are totally free,” Max adds. “There is no pressure from the label, they are just interested to hear the final result.” When reading about Lysistrata one can clearly see that journalists struggle to define the band’s musical style. What is it what they are doing? Something between noise-rock, emo, math-rock and post-hardcore are the stamps that most articles try to put on Lysistrata, each article copying a previous one. The band’s influences are quoted to range from Sonic Youth and Nirvana to Fugazi and At The Drive In, a band from El Paso, Texas. “We have tons of influences,” says the band. “We listen to a lot of bands from the 1990ies, but also more modern stuff. However nothing in particular.” In an attempt meant to be half serious but also to make a joke, Lysistrata call themselves “Post-Everything”. All we do is post, they say, everything has already been played and done before, in one way or another. “If you are indeed Post-Everything then you are in fact Pre-What?,” I want to know. “What can happen to Lysistrata in the future?” Ben has an idea: “Maybe Post-Everything is actually Pre-Nothing. Maybe even Pre-Everything and Nothing.” Despite their very young age - and perhaps precisely because of that - Lysistrata have a lot of self-confidence. They are certainly not bothered with finding a label and a drawer for their brand of music. It’s just their way of rock ’n’ roll. When I listened to Lysistrata to prepare for the interview I did it in the gym most of the time. Their energetic, in-your-face rock songs make you go faster on the treadmill and lift heavier weights. What is Georgy’s take on Lysistrata second album? Already back in August Georgy had his doubts. “Their new album comes out on October 18,” he said. “ I hope they can keep the bar up high (which is not doable in my opinion).” “What caught my attention in their debut album ‘The Thread’,” Georgy later told me, “is the balance that Lysistrata created between the different genres of music I grew up listening to. The album smoothly shifts from harsh noise to emo-like math-rock, with beautifully placed and timed chords and transitions that kept me on the edge of my seat. It’s chaotic and immature in the best of ways. As for the second album, I feel that they tried too hard to be more mature. It’s not as fun and flowy as their debut.” “We have transposed our setup from the rehearsal room onto the stage.” For my part I had much fun listening to Lysistrata’s second album and never got bored doing so. On stage Lysistrata are a powerhouse of their own. Too bad the concrete walls of the Dynamo club are a graveyard for any nuanced sound. The band’s energy is extremely engaging and their “singing à trois” makes them anything but choirboys. However what distinguishes Lysistrata from the rest of the rock pack are their long instrumental parts. Guitar, bass and drums are super tight and intertwined and at the end of a long dash to rock heaven and back, the difference between everything and nothing is all but blurred in my head. Lysistrata being so overwhelming on stage is also fueled by the way they set up the band when playing live. It is the same triangle formation that we know from FC Liverpool’s “trio infernal” of strikers Sadio Mané (let's say that's Max), Roberto Firmino (Ben) and Mohamed Salah (Théo). “On stage you are like locked in,” I ask the band. “What is going on inside the zone?” Ben again has the one-liner that explains it all. “We have transposed our setup from the rehearsal room onto the stage.” Théo and Max continue: “to truly play our music we need to look at each other often. It shows that we like a lot what we do. It has always been like that. We are like in a bulb. While conventional groups front the audience, we slightly turn to each other. Ultimately, the music happens between the musicians.” Lysistrata seem to be gone for a never ending world tour, playing gig after gig. Just last weekend they have been invited to the Blackwoodstock Festival in Nouvelle Calédonie (one of France’s overseas territories in the Pacific Ocean) and flew 30 hours to get there. They also have performed in Malaysia, Vietnam and China. Have they ever been threatened by a sex strike by their girlfriends because they spend too much time on the road? After all, Lysistrata is the historical figure that organized the sex strike in ancient Athens to stop the wars between Greece and Sparta. The band is laughing. “So far all is quiet on that front.” Lucky them, lucky us. The Lysistrata-show will go on. Very soon and very surely in a location near you. An architect walks into a bar… That’s how I intended to begin this article. But searching the internet for jokes starting with this phrase didn’t yield any satisfying results. Certainly not funny ones. Are architects too busy to go to bars? Or are they not funny? For my part I had much fun talking to the musicians of KOZO at Beirut’s Tunefork Studios between rehearsal sessions. And this despite the fact that, or maybe because, three of the five members of the band are architects. KOZO are funny but also very smart people. It may have been my smartest interview ever. A talk with KOZO makes you consult Wikipedia more often than an incontinent person rushes to the toilet in one day. The history of KOZO told in one sentence: they absorbed Filter Happier (another great Lebanese band). In reality KOZO is the result of a lot of courage. Andrew Georges (guitar) and Charbel Abou Chakra (bass) were playing in a band doing Sigur Ròs covers at the time. They were looking for a competent drummer to complement the band. Filter Happier on the other hand were a band “in suspension”; their singer had moved to France and their bassist to the USA. Andrew saw Filter Happier play, liked what he saw and mustered up the courage to talk to them (architects are also shy people). Elie el Khoury (drums) quickly agreed to join Andrew’s band and so did eventually Georgy Flouty and Camille Cabbebé (both guitars, and the two non-architects in KOZO). “I was particularly scared to talk to Georgy,” says Andrew during the interview. “He is a pro, he was in bands, he has been on tour in Europe and has this intimidating aura.” (Georgy: “What?”) Architects. Music. Enter Japan. On September 7, 2019, KOZO will launch their debut album “Tokyo Metabolist Syndrome” at the SoundsGood Music Festival in Rayfoun and it’s an unusual album. KOZO may not call it that way but it’s a concept album celebrating metabolism, a post-war Japanese architectural movement, and comparing it to the state of architecture in Lebanon. “Actually, I don’t like the term concept albums,” Andrew says. “it reminds me of herbal, cheesy records from the 1970s.” Charbel and Andrew are both architecture buffs who post regularly about their passion on Facebook. For the rest of us it’s time for a crash course in metabolism. Metabolism was a movement that explored methods of large-scale reconstruction for Japan’s cities severely damaged by the war. Between the 1950s and 1970s, Metabolists like Fumihiko Maki, Kenzo Tange and Kisho Kurokawa emphasized the need for Japanese architects to emulate organic systems in their designs for urban megastructures, highlighting how metabolisms in complex organisms work to maintain living cells (I told you that KOZO were a smart band). In short, buildings and structures (and interestingly enough KOZO means structure in Japanese language) were seen as living bodies consisting of self-sustaining and self-adapting modules. Now how does the music of KOZO relate to the architecture of metabolism? “I tell you how it started,” says Elie. “We started covering songs from bands we liked and from that we figured out our own sound. It was and still is an entire process.” Andrew jumps in: “the idea of architecture in music is about sticking to a process. And accepting the little inconsistencies that happen when you stick to a process. You get those random results at times. We abuse these and make them part of our music.." The music of KOZO is heavy on drums, bass and guitars and their songs often don’t fit the usual radio format. They take their time exploring the landscapes and horizons that lie ahead of them. In exemplary math rock tradition it is music made by nerds that doesn’t sound too nerdy after all. “I like when things don’t sound like you expect them to,” Andrew explains. “With KOZO, it’s my doom metal guitar versus their (Camille’s and Georgy’s) sparkly dream pop riffs. And it works!” Performing the music live feels very physical, Elie adds. “For all of us it is a mental exercise because we use a lot of odd time signatures.” The band admits that they tend to overthink their music when in the studio. “But when we play it live,” says Elie, “that’s when I feel that we really unleash.” “There is a lot of freedom when playing with KOZO. I am not restricted to anything."

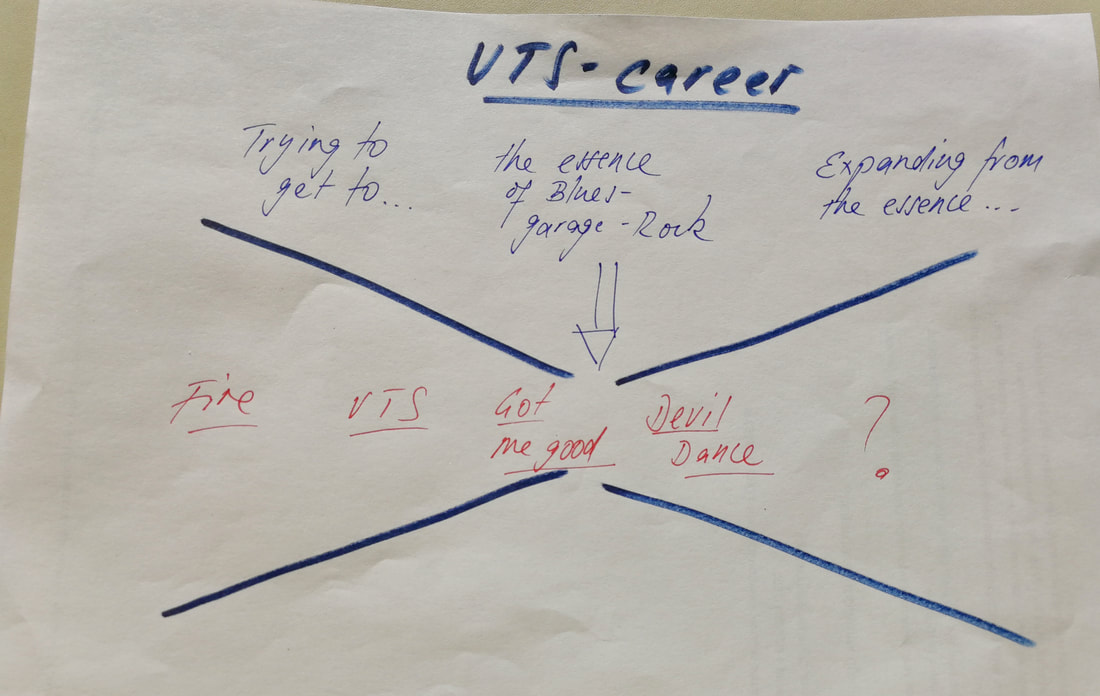

Many bands play songs with a “verse - chorus - verse - chorus” schema. KOZO aim to break this established pattern in order to maneuver out of their comfort zone. However there is a side effect: with a regular song you have a place to land on with the song. With songs made by KOZO this comfortable landing spot is gone, for both the band and the listeners. “For me there is a lot of freedom when playing with KOZO,” says Camille. “I am not restricted to anything and I never strum an actual chord. I come in for a bit and then I go out again.”

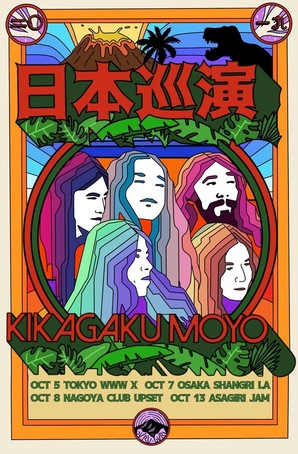

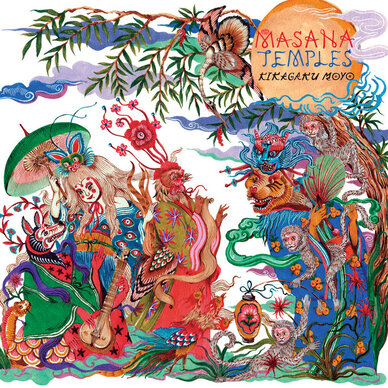

So how do the listeners react to KOZO’s music? They don’t know when to clap, says Georgy, jokingly. When performing in the north of Lebanon as part of a school event, the kids left the concert but the parents stayed. The band has had great feedback from people whose demographics they didn’t have on their radar. And Camille reveals one of the best kept secrets about KOZO: when they sing (and on many songs they don’t), they sing in Arabic! “For a long time,” Camille tells me, “all my friends thought that we sing in Japanese. Because they looked at the songs titles and assumed that the lyrics would be in Japanese." The song titles are indeed very Japanese and read like a history of the metabolist movement. “Tange” (referring to Kenzo Tange, one of the founders of metabolism), “Osaka 70” (the world exposition in 1970 for which Tange had planned the site), “Capsule Tower” (the icon of metabolism in the Ginza district of Tokyo) and “Tokyo Bay Plan” (Tange’s proposal for extending Tokyo into Tokyo Bay): what is this infatuation that KOZO have with Japan? They have never visited the country and they don’t even speak Japanese (but according to Soundcloud we now have fans in Japan, says Georgy). Andrew takes a deep breath. “As architects,” he explains, “we became enamoured with the concept of metabolist architecture. And then we realized what Japan did after the war and what we did in Lebanon. We sadly ignored whatever potential was present at a certain time and let it slip away. KOZO’s music is about implying our naive understanding of this land - Japan - that is literally far away and dreaming of an architecture for our land that has the same weight as the metabolists had for Japan. People who built futures in the now distant past that we are imagining for our own future, in perhaps the most childish way.” If you have 6:44 minutes to truly understand what Andrew Georges means, then listen to “Tokyo Bay Plan”, the last song on KOZO’s album. If you have only twenty seconds to spare, then fast forward to the end of the same song and focus on Elie firing a final salvo on the drums eight seconds before the end. You will know. That’s Lebanon, that’s the Orient, that’s the land of damnation and salvation, in a musical nutshell. KOZO’s music, although mostly instrumental and without words, is more political than the music of many bands that have been driven to the gallows lately. Lebanese are a people suffering from Stockholm syndrome: they have been conditioned to be in love with their worst enemy, themselves. KOZO are aware of this but don’t know better than to hang in there. “We are a Beirut-based band,” they say, “we couldn’t write our songs outside Beirut.” This was certainly true for the first album. Yalla guys, you now are ready to leave the cocoon. Come to Europe, go to Japan, play concerts, compose new songs, the world is yours. Japanese love surprises. KOZO would definitely be one of them. Yesterday evening in Oslo, tonight in Bern, tomorrow afternoon playing at a festival on an alp in the Valais: Kikagaku Moyo don’t take it easy to bring their music to the people. "Last night we did not sleep at all," Go Kurosawa tells me before the concert at ISC in Bern, Switzerland. “We finished the concert in Oslo at 2am, at 4am we were back at the hotel and two hours later we had to leave for the airport.” "What do you do to ease the stress when touring? Working out?,” I ask Go. "No, I'm the drummer”, he replies, "that's already pretty physical. I relax when I play on stage. And when I'm really tired I tell myself that I’m extremely lucky to be able to do what I love to do." Kikagaku Moyo have been around since 2012 when the band started out busking on the streets of Tokyo. Their last and best album so far, "Masana Temples", is from 2018, recorded and produced in Portugal. Besides Go, the band consists of his brother Ryu on sitar, Tomo Katsurada on guitar and all sorts of percussion instruments, Daoud Popal on guitar and Kotsu Guy on bass. Kikagaku Moyo play psychedelic music: they like to improvise and take their time for long songs. Psychedelic music dates back to a time in the 1960s when artists believed that drugs would make their music sound better. Psychedelic drugs such as LSD led to an increased consciousness among consumers, which then had an effect on the music that was composed and played under the influence of these drugs. On the other hand, this music also had the effect of deepening and expanding the experience of the drugs. It was the classic example of a mutual leverage that was not always understood by outsiders. "Can you play psychedelic music without drugs?”, I ask Go. "I think so”, he replies. "In the past I also took drugs, but not anymore. It's about experimenting with your consciousness. You can achieve the desired state without drugs. Sure, the drugs have played an important role in the history of psychedelic music, but reducing everything to drugs would be too much of a shortcut. Psychedelic is like a philosophy: it's also about the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, it's about literature and also about fashion.” (Kikagaku Moyo are indeed a band with style and undoubtedly look good. GQ recently hyped them as “they might be the best-dressed band of the decade.") "Everything is just music and there is no ‘me’ anymore.” The desired mental state, however, can not be reached through two-minute songs. The true trip only begins when the music draws longer. Kikagaku Moyo then try to focus five individuals on one thing, to create something unique under this burning glass. This is a kind of collective meditation and as if in a trance the band shoves forward with their music. "For me as a drummer, this condition is relatively easy to achieve," says Go. "I'm sitting in the back of the stage, in the dark, and can plunge into my own zone, away from the audience. I stop thinking and my arms and hands work automatically. Everything is just music and there is no ‘me’ anymore.” Right from the start of the concert the audience falls into an "instant trance". A repetitive bass line, strumming guitars, Go who sits at the drums and sings: The tense drowsiness of the band goes well with the sleepwalking spirituality of their music. A few minutes into the first song the heads of the listeners already bob dangerously. Kikagaku Moyo are constantly looking for a unification in sound until a groovy bassline sets in and leads the band out of their self-imposed impasse. For some songs the drums are left aside. Tomo has all sorts of sound gadgets in his repertoire - triangle, gongs, cowbells - and Go tries his hand at the flute. These are special effects almost like in filmmaking. My imagination goes into overdrive as well with Kikagaku Moyo’s brand of music. And this not only in a concert setting but already when I listen to their album. Let’s take "Dripping Sun”, the second song from the Masana Temples album. It starts out as a Sergio-Leone spaghetti western and then quickly merges into a 1970s cop movie (it could also be something by Quentin Tarantino, "Jackie Brown" maybe). Later I see a car chase (or even a helicopter overflight?), just before the songs fades quietly back into suburban Japan, to people who wait for the bus while enjoying the sun (if they had the leisure to do so). The city pop of Tatsuro Yamashita trickles down their ears through their Sony walkmen. However the situation is more serious than one thinks. The guitars are racing in California and the last dolphins are dancing far out in the sea. At the end of “Dripping Sun” we are back in the police film which is slowly heading towards a showdown. The hero thinks back to Japan one last time. Then the sun goes down for him as well. For once in Bern, Guillaume Hoarau, the star striker of the local football club, is not the favorite player of the masses. Tonight it's Daoud Popal, Kikagaku Moyo’s guitarist. His fuzz guitar keeps cutting deep furrows in the feel-good-field of non-violent music that his colleagues till with a smile. He is assisted by Ryu Kurosawa's sitar. "The sitar is really a special instrument, it could almost replace an entire band," says Go Kurosawa. "There used to be quite a few bands with sitars. But we want the sitar not to sound like Indian kitsch, but modern. That's why we use the sitar like a guitar, with amplifiers and effect pedals. I assume that Greta Thunberg listens to a lot of psychedelic music. If not, she should start to do so, to give her message even more depth. Mindfulness - towards fellow human beings, towards nature, towards oneself - is contemporary. In this sense, psychedelic music is also contemporary. The message of Kikagaku Moyo may be more necessary today than it was then, when this music had its big bang. It goes beyond a mere "Peace and Love". It means, in the truest sense of the Greek origin of psychedelic, to let the soul manifest itself and to develop the potential of the human mind further. Then we will be able to again give little things the appreciation they deserve. This may seem like little. But we have to start somewhere. from The Open Enso archives. Photos: May Arida  Three concerts in a row in one of the music capitals of the world: that’s why Sandra Arslanian and Sam Wehbi came to London in this early September of 2018. Sandra and Sam are members of Sandmoon, an indie pop/folk and sometimes rock band from Beirut Lebanon. Sandra founded the band eight years ago, a few years after she came back to Lebanon from Belgium where she grew up; she writes all the songs, sings and plays the ukulele, the guitar and the keyboard. Sam plays the lead guitar, particularly when Sandmoon perform live. The rest of the band couldn't make the trip to London, not least because of visa issues. We arrive in a sunny but windy London on Friday afternoon. We: that are yours truly reporter from Switzerland and May, a photographer who is originally from Beirut, like Sandra and Sam. Both of us have known Sandra for quite some time, closely following her career, from releasing three albums and an EP to winning a Lebanese Movie Award in 2017 for composing the score of Philippe Aractingi’s Listen. We meet Sandra and Sam in Katja Rosenberg’s apartment in Walthamstow in northern London. Katja’s flat is small and well stuffed, but this is London where space is rare and expensive. For this weekend the apartment is Sandmoon’s home base. Yesterday’s concert in a chapel was amazing, Sandra gives us the update after we all sit down. Two dozen persons only, but the place was sold out. We played for eighty minutes and the people wouldn’t let us go. Now we are curious what tonight’s concert will bring. It will be a Sofar event at a private place in Bethnal Green. "It is really nice to play in front of people who actually listen to the music." On our way to the Sofar concert Sandra hands out Stimorol chewing gums to everybody. Tonight, Sandra says, I will be the great unknown. Nobody this evening will ever have heard of Sandmoon or Sandra Arslanian. I like the idea. Our music, she explains, might not work in Spain. But in Portugal, with all their Fado, it might. Here in London our music definitely works, people like what we do and how we sound. Are you fed up with Lebanon and the Lebanese audience?, I ask Sandra. Not really, she says. But of course Lebanon is a very small market for English lyrics pop and rock music. And there is another thing: unfortunately in Lebanon only a few people go to see concerts because of the music. They go because others go too and it then becomes a social event. It’s like a herd moving from place to place. It is really nice to play in front of people who actually listen to the music. Sofar tonight takes place at the loft style apartment of Casey and his girlfriend Rachel. Sandmoon start their concert with Home, one of their trademark songs. Sandra sings without microphone, without nothing, to an audience on the floor and on sofas with all eyes on her. Sam is her ideal musical partner, getting the best out of a rusty acoustic guitar that he had to borrow from a friend. With the small combo, Sandmoon depend even more than usual on Sandra’s voice and performance. The audience is like spellbound, particularly when Sandmoon perform The Answer, a song from last year’s recording session in Berlin. Then they play Walk, an old favorite, but not Temptation, a newer song that wails like a prayer. It’s Friday night and the audience asks for something "more party". After the show Sandra is sweaty and exhausted. The public slowly leaves the apartment, they very much liked what they got. We pick up some Chinese food at a takeaway in Walthamstow. Then we all huddle again in Katja’s apartment and eat. "Me improvising on Bach, what the hell!" The next day, when we meet again, Sandra is in a good mood, offering Belgian chocolate to everybody. Sam lies on the bed and fingers around on his electric guitar before he goes into a catchy rock tune from his own Uncle Sam band in Beirut. In the meantime Katja is busy doing some household work, watering plants and hanging laundry. Katja was born in Germany but lives in London since 1998, working as a freelance powerpoint guru and an organizer of art events. It is thanks to her that Sandmoon play three concerts in London. Katja sits down at her piano, jammed between the bed and the wall, and plays Bach. Sam plays along on the guitar, still on the bed, his eyes staring at the ceiling. Me improvising on Bach, Sam says afterwards, what the hell! Saturday night’s venue is the Hornbeam Café, an organic, authentic neighborhood café and also a community center. The Hornbeam is a place similar to the Onomatopoeia in Beirut where Sandmoon like to play. What is Sandra for you?, I ask Sam outside the café, just before the show. Sandra is like a mother to me, Sam says. She is a great teacher; it’s three years now that I am playing with her. She makes me control myself better, musically and also in general. I am still relatively young, Sam explains, and therefore I have a tendency for wanting to storm the sky. Even without the full band, Sandmoon cover a lot of musical ground with their performance this evening. Sandra clearly has made the transition from recording artist to performing artist. She is at ease on stage, displays a lot of self confidence and is closer to the audience than I had ever seen her. During Sandmoon’s concert all their videos are projected in an endless loop on a screen behind Sandra and Sam. The audience sees images of Beirut in the 1960s and of people protesting the political order in recent years. The video of Sandmoon’s 2017 single Shiny Star passes by and Pierre Geagea dances in Beirut Mansion to the music of Time Has Yet To Come. Seeing it like this, from A to Z in one sequence, it is an impressive body of work. On our way back to the apartment we stop for a late night dinner at Thainese, an Asian restaurant on Walthamstow’s main road. We talk about Prince and Bowie, Sandra’s musical heroes, and also about Fentanyl and discuss if pain killers should be classified and treated as drugs. For Sunday lunch we again go to Walthamstow’s pedestrian area and to a Bulgarian steakhouse. What is the way ahead for Sandmoon?, I ask Sandra. Could hiring local musicians in London be possible, to play future concerts here with a full band? It could, Sandra replies. However it is hard for me to play with strangers. Sam and me for instance, that’s like an osmosis. In addition to not being strangers, Lebanese musicians are all shaped by the same experience: Lebanon. Could musicians from London emulate this experience? Often this is an experience of war and it is also reflected in Sandmoon’s current setlist going from songs off the first album raW to Masters of War, a Bob Dylan cover. I don’t know the war that well myself, Sandra says, at least not first hand. In 2006 I was abroad and when my family left Lebanon because of the civil war, I was only seven months old. Does it matter? Despite not personally being there, war and the consequences of it are profoundly anchored in Sandra’s DNA. Back in Switzerland Sandra messages me that Sandmoon will soon start to record new songs, with an aim to have a new album out in 2019. Sandra has been very creative lately, also inspired by the good experience she had playing in London. She was in a flow and has written many songs that now need to be developed, refined and recorded. And: We clearly aim for an another Sandmoon visit to London soon, Sandra says. Londoners dig the melancholic side of Sandmoon’s music and they always love a good storyteller. And that’s precisely why Sandmoon came to London: to find a new audience and new opportunities to spread their message and their musical love. Sandmoon will be back in London; new concerts are scheduled for August of 2019. As for the new album: all the songs have been written - it will be somewhat of a new direction for Sandmoon - two songs have already been recorded and "Fiery Observation", the first video off the forthcoming album "Put a Gun/Commotion", has just come online. For Sandmoon, it's a road that never ends. "Good thing that I am tattooed. Because from what I read and saw, the women of Velvet Two Stripes, who I will meet in an hour for an interview, appear to be a lot of trouble. On band photos their arms are covered with tattoos, cigarettes are dangling from their mouths and they seem to drink beer and fancy whiskey a lot. I will have to show off my own tattoos to be credible enough to talk to them halfway at eye level. These are the kinds of clichés that really piss off Sophie Diggelmann, Sara Diggelmann and Franca Mock, the three women of Velvet Two Stripes. Yes, we drink a shot of whiskey from time to time and we smoke cigarettes. Yes, we are loud and we like to laugh. So what! More annoying than this is only another widespread platitude: that Velvet Two Stripes is an all female band (or even worse: a girl group). Excuse me? Has anyone ever called the Rolling Stones a boy band? Let us better talk about music and "Devil Dance” then, the new album by Velvet Two Stripes, before VTS will hit the stage tonight in Berne, Switzerland. The album was recorded in Berlin, in the famous Hansa Studios; it is the temporarily summit of a road that Velvet Two Stripes have traveled since their first EP "Fire". "The songs of 'Devil Dance' sound different than you used to sound,” I ask the band, “how come?" Sara is the quickest to reply. “We are better at songwriting now. We have learned how to write better songs. This was the biggest step for us compared to before. Our new songs are very differently constructed than the previous ones." Songwriting by Velvet Two Stripes is often the result of jam sessions; everyone joins in and eventually, somehow, a musical idea emerges which is followed up. Most of the times a guitar riff coming from Sara is involved. "How many riffs does a guitarist’s life have?,” I ask Sara. She laughs. "I do not know if there is a limit,” she says. "RPL, riffs per life, so to speak. You can always play the same riff, but when the bass does something else then the riff itself will sound different as well." Sara started her life as a guitar player with a Fender Stratocaster and later switched to a Telecaster. Today she plays a Gibson ES-335 from the year 1968. Big guitar heroes like Eric Clapton, B.B. King and Dave Grohl play (or have played) the same model. Franca’s bass, a Fender Precision, is vintage too and dates back to 1972. "Only your voice is relatively young and is made in 1993,” I am teasing Sophie. "Who knows,” she answers slyly, "maybe it is the reincarnation of an older voice." "Janis Joplin maybe?" "In any case, I already shouted in 1993." Sophie Diggelmann knows her raspy rock voice well and knows how to keep it in shape. The important thing is, says Sophie, that she listens to her own body. Sophie senses how much her voice can bear and thus gets through the concerts without becoming hoarse. And should her voice nevertheless be a little knocked out then there is always tea. The cigarettes she smokes are not really good for her voice, Sophie is well aware of that, "but what else can you do if you must kill time before concerts?” Sophie studies art and is also responsible for the artwork of Velvet Two Stripes. The cover of “Devil Dance” is her work. And she also designed the VTS T-shirt that was a goodie in the band’s crowdfunding campaign last year and which I am wearing for the interview tonight. "In Beirut they almost wanted to rip your T-shirt off my body,” I say, "my friends there loved it that much." “Yes exactly, Beirut,” says Sara. “In one of your messages you asked us about the oriental-sounding guitar solo that I play on 'Sister Mercy'. The reason is that a few years ago I visited Beirut for two weeks and got to play the oud, the Arabic lute. I was inspired so much by this that I have played some oriental sounds in the studio when recording the album, but with an electric guitar.” Indeed: the oriental notes of "Sister Mercy" could indicate a future progression of the band. And also the noise elements that are present in several corners of "Devil Dance", especially in the last 30 seconds of "My Own Game”. Sure thing, the blues will always be the musical root of Velvet Two Stripes, but if we dive into the blues even more that we already did, the band says, "we can soon collaborate with Philipp Fankhauser." Anyway, Velvet Two Stripes don’t see themselves as a blues band, but rather as a rock band. As a blues garage rock band that likes to play hard and loud. With "Devil Dance" they have created the essence of this style, they have found the state they desire. The songs of Velvet Two Stripes have become more straightforward, without background vocals, pop elements and drum computers. VTS achieve a maximum effect with a reduced-to-the-max attitude. “With Velvet Two Stripes there is an ongoing development happening from the inside." Where is the musical journey of Velvet Two Stripes heading to? What's next in their career? I'm getting a rudimentary graphic out of my pocket that I drew in preparation for this interview. It shows Velvet Two Stripes in search of their true sound - which they have now found with "Devil Dance" - and the possibility, starting from this reference point, to further develop the sound of the band. The three women like the drawing. "On the new album,” says Sara, "we've become bolder and dare to try out new things. Take 'Lizard Queen’ as an example: I have been playing this rolling guitar part with the deep bass sounds for ages at our soundchecks. So far, Sophie and Franca always found that it was boring. But now the time was right and we tried to build a song around this part." “With Velvet Two Stripes there is an ongoing development happening from the inside,” Sara continues. "We find each other more and more." Hell would rather become Antarctica than "Devil Dance" not becoming a success. Songs from the album can now be found on various playlists on Spotify. As a result, the number of monthly clicks for Velvet Two Stripes has jumped from 800 to 82,000. The band has only a limited idea of how this all happened, who in the world of Spotify digs Velvet Two Stripes so much and integrates them into playlists, even in Canada. They also don’t know who is responsible for giving VTS airplay on a Dutch radio station. They didn’t pay anybody to do this. But by all means it’s great.

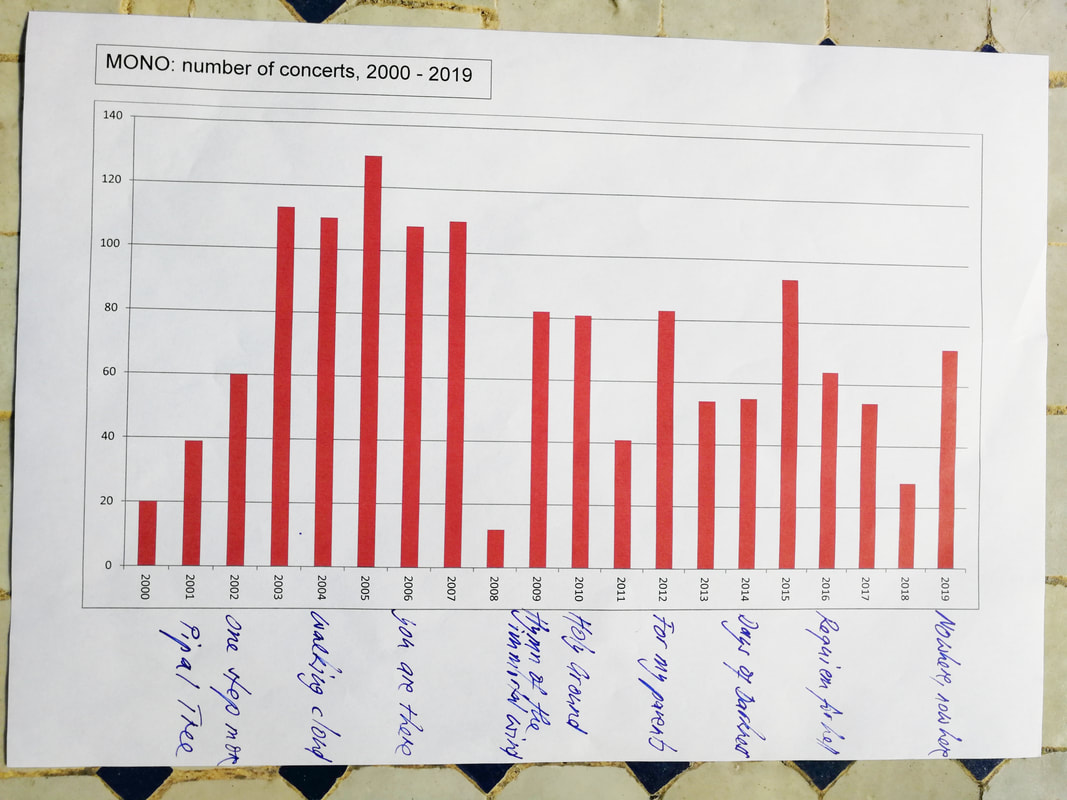

At the end of our conversation Sara returns to my sketchy mind map. "Nobody has ever made such a drawing for us,” she says. "Now I'm really excited to find out where our journey will lead us." Velvet Two Stripes will be on tour all summer in Switzerland, Germany and Austria. For details and dates check out the band's website. “Let me tell you a crazy story”, says Taka Goto, head of MONO, the Japanese post rock band, shortly before their concert in Zurich on April 28, 2019. “A story that happened a long time ago. First I received an email from a fan in Iraq. He wrote to me that he is listening to MONO all night long because only thanks to our music he is able to cope with the American bombs that strike his city incessantly. One week later I got an email from an American soldier stationed in Iraq. He told me the same thing: only thanks to MONO he endures the war in Iraq. Crazy, no?” Since 20 years the Japanese of MONO save the world. During this time they have released ten albums and played 1368 concerts. The concert in Zurich is number 1369. It is a special mix that distinguishes MONO and has always fascinated their fans. A mixture of breathless melancholy full of dramatic melodies paired with deafening musical climbs towards ecstasy. The music of MONO works on the principle of hope: our world is evil, but MONO gives you the weapons, gives you the therapy, to defeat the evil. Also Taka is saved by his own music. When he composes, he tells me, he dives deep into that damned darkness that sometimes surrounds him, trying to find a light. His songs have become his own medicine. ”Why do you need so much salvation?”, I ask him. "Because the world is so complicated”, he says. "Actually, the recipe in Buddhism is quite simple: respect each other, love each other, help each other. However this can be very difficult. That's what I try to explain with my music.” “I don’t trust what I see. There are things that we only can feel.” MONO is an instrumental band but on their website (one of the richtest and most informative I've ever seen of a band), they are very eloquent with words. Here Taka describes the idea behind “Transcendental” in words that would suit a church chaplain. The track is about life and death and regeneration, Taka explains. When our bodies decay and decompose in death, and thus become the seeds for future generations, our souls will journey together into our new eternal life. “Where does your spirituality come from”, I ask Taka. “I don’t trust what I see. There are things that we only can feel. The new album from MONO is called "Nowhere Now Here" and for Taka it feels like a second debut album. Two years ago MONO had huge problems with their management and at the same time the drummer left the band. The future of the band was seriously threatened; MONO was like a tired creature, Taka says: "No drummer, no management, no money." This dark period is also the reason why on the new album for the first time in the career of MONO there is singing. "One day Tamaki, our bassist, called me and told me I can’t breathe anymore, there are too many stories going around. And I told her, everything will be fine, trust me. The band will live on and we will also find a new drummer.” Finally, Taka wrote the song" Breathe”, based on the idea that Tamaki cannot breathe. And now she sings this song on stage! The new drummer’s name is Dahm and he is American. He fits frictionlessly into the well lubricated musical clockwork of MONO, also at the concert in Zurich. The stage is dark and the musicians can be recognized only dimly, they are shady faces in the backlight of the spotlights. The concert starts with a crashing noise storm, with thunder and lightning coming from "After You Comes the Flood". We have just celebrated Easter, the feast of silence, where deep mourning is followed by the joyful resurrection. And now MONO come to us with their din close to the pain barrier. Are these opposites? No, not at all. The latter is just a loud version of the former. Taka’s idol is Ludwig von Beethoven. “I understand each of his works”, he says, “and why he needed to write it.” Taka writes music because he must. Because he wants to create something, even as a child, that only he can create exactly like that. And even today, after 20 years of MONO, he is still grateful that he can fully concentrate on the arts with his life. He enjoys every day, even the days on tour, and there are many. "At the beginning of our career, in the early 2000s”, says Taka, "we played a large number of concerts, over a hundred a year, especially in the USA. At that time there was no MONO website, no social media and we had to somehow make a name for ourselves.” Only in 2008 did Taka Goto take a six-month break to compose "Hymn to the Immortal Wind," the album that fans almost unanimously call MONO’s masterpiece. How does Taka survive MONO’s never ending tour? He doesn’t go to the gym and he is not twenty anymore either. “True", says Taka, "my body is slowly getting older. It is the energy of our audience that drives us forward. Sometimes we go on stage super tired and boom!, the energy hits back at us from the public and we go again. Maybe we will even reach a new record of concerts played this year.”

The French composer Nadia Boulanger once said (to Quincy Jones), "your music can never be more or less than you are as a human being". Nadia Boulanger could have said this to Taka Goto; he is a prime example of her theory. Taka (and Yoda and Tamaki and Dahm) is MONO and MONO is Taka. There is no difference between the artist and his art, everything is one, everything is melting. However: with MONO there is no difference between the artist and his audience either. Anyone who attends a MONO concert comes out a changed person. It is this destructive yet creative power of their music that grabs you. After all the frustrations and the fear they went through, the band entered the studio to record their current album with a lot of rage; when MONO play live this anger is still perceptible today. But there is also this catharsis, through silence and through volume, that MONO creates and which lets you see the white light at the end of your own black tunnel. MONO concerts are mind blowing, in the truest meaning of the expression. You believe your brain is going to explode. You are transported and distorted, blasted and lambasted. You walk through damnation and receive salvation. You too are saved by MONO. |

EditorKurt is based in Bern and Beirut is his second home. Always looking for that special angle, he digs deep into people, their stories and creations, with a sweet spot for music. Archives

September 2020

Categories

All

I'd love to discover you. Share your creations here.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed