Menu

|

At one point, loser Jimmy McGill became cunning freestyle lawyer Saul Goodman; that was around 2005, in the prequel to the TV series Breaking Bad. At one point Lizzy Grant from the trailer park became singer Lana Del Rey. That was around 2011, before her musical breakthrough with the album Born To Die. In an interview for Vogue she explained: "I wanted a name I could shape the music towards. Lana Del Rey reminded me of the glamour of the seaside. It sounded gorgeous coming off the tip of the tongue." And today, in 2020, Mei-Siang Chou, who already performed on stage as a singer behind Bobby McFerrin and Anastacia, becomes the solo artist Meira Loom, who delights the world with her own songs in the field of soul, neo soul and jazz and who may be considered - without exaggeration - as one of the best voices in Switzerland. But who is Meira Loom actually? And how does someone come to call herself that way? We start our search for Meira Loom on www.baby-vornamen.de, a German website for baby names. Meira, it is said here, is the one who comes from the light, the enlightened one. Elsewhere, Meira is equated with the star of the ocean or simply seen as the short form of the Spanish maravillosa and translated as “wonderful”. Visitors to the website associate the name Meira with modern, attractive and successful. So far so good, with her first name, Meira Loom is on the safe side. Things get more complicated with Loom. In English, to loom stands for something threatening that comes up and then hangs over you. Thunderclouds for example, or even a UFO. However: Who would object to a star of the ocean hanging over him or her? "Loom combined with Meira, I found the vowel-color combination very harmonious (ei & a & oo)”, says Meira Loom. "So it was more of an acoustic composition than a content-based one. Just like music. Moreover, Loom is also one of my favorite songs by Ani di Franco.” As a child, Mei-Siang Chou practiced the hurdles in the garden for hours and jumped 5.10 meters in the long jump (as a left-footer!). Other biographical facts from her youth are no longer relevant today to explain Meira Loom. Was she able to do handstands as a child? Was she good at grammar? Did she never miss an episode of the Mini Playback Show? Why would that still matter today? Meira Loom lives in Berne these days, is a singer and musician and finds her resting pulse when she sits down by the Aare river and looks into the depths of the water. She now understands what she is able to achieve as an artist. Now she dares to try things that she didn’t dare to do before. Before that, self-doubt accompanied her on her path and prevented her from reaching her full potential. Of course, making art is always a risk, Meira Loom is aware of that. Those who are creative expose themselves to criticism and risk not pleasing everyone. But she has dropped her fears of failing, has become courageous and persistently aims at her newly defined goals. Instead of the Café Marta in Berne, she now doesn’t mind to go as far as the Royal Albert Hall in London. As with Lana Del Rey, the art figure Meira Loom is increasingly becoming a real figure, the only figure. The name becomes the program. “My former comfort zones are worthless today. They are well past their expiration date.”

The reason for Meira Loom's transformation is her debut album Letting Go, which was released on August 28, 2020. The album contains eleven carefully arranged tracks that she wrote herself, with one exception. Where Lana Del Rey's Born To Die is melodramatic and sad in a certain way, as the title suggests, Letting Go is an invitation to a self-determined life. Meira Loom sings about letting go and self-indulgence, and about toxic relationships and outdated obsessions that she leaves behind. “My former comfort zones are worthless today,” she says. “they are well past their expiration date.”

Meira Loom recorded her album at home in her studio. She brought the baby into the world almost all by herself - but that doesn't mean that she became a single mother. The child and her mother are cared for from different sides and enjoy a very happy time. In the process, Meira Loom has even learned to appreciate teamwork. Sure, here and there, one would have wished that the album had been produced with a richer sound. Letting Go was created with the "moyens de bord", as the French say, with the means available. Hence it is above all a statement for Meira Loom's versatile voice, which can burn powerfully, with no restrictions, only to caress the ear right afterwards, gently and velvety. When someone moves out of his or her home, like Meira Loom, who now moves out of Mei-Siang Chou, this person doesn’t usually move into a five-room apartment with two bathrooms right away. That has to develop. "There is enough for everyone - including myself" is what Meira Loom conjures up on her debut album and these lines are symbolic of her new mindset. There is enough talent in the world and Meira Loom has got a lot of it. There is enough love in the world and a lot of it goes to Berne: because of Meira Loom and for Letting Go.

0 Comments

Maya Aghniadis loves to invent her own language. She comments good news with Bombastic! or Boom! and refers to all kinds of things and activities as “shizzle” (which, for the Cambridge dictionary, is “a more polite word used instead of the word shit”). Some may say this is gibberish and also will declare it gibberish when it comes to Flugen, the name of Maya Aghniadis’ musical project. According to the Urban Dictionary, Flugen (actual spelling Flügen) means everything and nothing. Maya herself said it in an interview with Project Revolver in 2019: Flugen was a word she used a lot when she didn’t know what to say. She has always been better with music than with words.

And then again, Flugen (the expression) is more than anything and everything. It is what you make of it. For some Flugen is synonymous for a relaxed lifestyle, for others it’s basically just going with life and enjoying the hell out of it. Do not get me wrong: that is not to say that Maya Aghniadis hasn’t any serious ambitions for Flugen (the music). That is not to say that Maya is careless and too easy going on herself when creating music. Quite to the contrary. However, for this writer, Poupayee, Flugen’s new album is the first Flugen record that fully matches the musical goals that Maya Aghniadis has set for herself. Poupayee is not anything, but it is everything and it defines a new musical lifestyle called ethno-electro-jazz. Also in music Maya Aghniadis has invented her own language.

Poupayee has to be viewed and consumed as an album, as a whole, and not as a compilation of songs. One thing leads to another, the sequence of the tracks matters - the track you are hearing, the track before and the track afterwards - and the entire experience when listening to Poupayee is bigger than the sum of its single tracks. “Poupayee tells the story of the different states that a mind can go through,” says Maya Aghniadis. “With every step we come closer to surrender and release to all the shapes of truth.” For impatient characters such as myself, listening to Flugen can be a challenge. Maya Aghniadis has a unique way of composing her music in an almost meditation-like fashion, building up momentum and tension very slowly, very delicately, only step by step. Sometimes it feels like lying on the beach in a hammock, smoking a joint and looking out to the calm sea and waiting for the next wave to break at the shore. This can take a while, but just observing the serenity of the sea brings you the ease of mind that you had been yearning for. When the wave finally arrives, it just might be the next tsunami that surprises you once again. You may run from your hammock but you cannot hide from Flugen’s beats. Maya Aghniadis knows that for some listeners her music feels wobbly. Like a dancer on a rope cautiously trying to hold his balance before he sets one foot forward to precariously move ahead. “That’s not wobbly, that’s just the Flugen craziness”, she says, laughing. Maya is different from the rest of us and so is her music. The music of Poupayee is mostly based on synthesizers and piano, at times underlaid with heavy beats that can probably be felt down on ground floor (I live on fourth floor). Add to this an occasional flute that represents the ethno part of the Flugen sound and the clarinet of Pol Seif. The album starts out rather calm and peaceful but by track three and four - Shades of Blues and Different Ways - hints and flavors of a more dangerous world start to emerge. At first, one barely notices them until we arrive at The Lodge (track 6) where our conscious meets the subconscious and Flugen makes us lose ourselves to a repetitive and broken beat. We then realize that Something Wild (track 7) is bound to happen and that the Peak (track 8) is near where will discover our sensual selfs. "Words are not the essence!"

Such a journey to the truth is never easy as Where To? (track 9) demonstrates. Marwan Tohme (of Lebanon’s indie rock band Postcards) adds his ominous guitar to the Flugen sound and makes this track dark and frightening. We are almost inclined to turn around, not daring to stay the course and to break through this heart of darkness. This would have been a grave error because the final track of Flugen’s new album - Surrender & Release - introduces us to a new world where beautiful melodies fill the air and love takes over.

“Words are not the essence,” Maya Aghniadis explains when describing Poupayee, “gibberish sounds such as the title track itself can bring out the truth more than words”. Music and the emotions it is able to evoke and convey is like a foam, filling the empty spaces in our bodies and our minds. Words can never reach where music can. It is said that children and fools always speak the truth. If the truth lies in gibberish words such as Boom!, Flugen and Poupayee, and in the music these words provoke and entail, then I happily admit: I’m a fool! Poupayee is indeed BOMBASTIC. You can listen to Poupayee on all streaming platforms worldwide. Go here. They are clever wise guys indeed, Lea Heimann and Katharina Reidy. They name their band Paradisco and someone like me sees Italian gelati in front of him and thinks, okay, now that's a nice play on words with Paradiso and Disco. But when you prepare to interview the two women, a synapse suddenly snaps in your brain: watch out! Wasn’t there something with Para? This is not quite as innocent as it sounded at first, just think of paramilitary and parasites. And paranoia. The story of Paradisco is quickly told: Lea has always played music, Katharina never did. The two friends went to concerts together a lot. And then, in 2015, Lea was tired of her saxophone - she was now more interested in electronica, in sounds and in noises - and almost at the same time Katharina grabbed the app of her musician friend and produced beats and loops with it herself. Three months later they were on stage for the first time at Fri-Son in Fribourg, Switzerland, as Paradisco. With their music, Paradisco want to merge the digital and the analog into a fusion. "We are looking for tones, for sound structures that together form a sphere," says Lea. "We want to provoke a digital-analog approach in which the listener no longer realizes which is one and what is the other." The sphere is an important image when Paradisco talk about their music, especially for Lea. If you think of a glittering disco ball, you're missing the point again, as I did at the beginning of my acquaintance with Paradisco. "The sphere," says Lea, "parabolically stands for an emotion that we want to convey, a conscious, intense feeling." "We want to draw our listeners into the sphere and offer them a new world," Katharina adds. A new world in which love would probably be the priority state. "Love is my lifestyle" is the title of Paradisco's first album, released in 2019. (In female understatement, Paradisco call their record "an EP", even though it contains six songs and all of them are better than the life's work of many a highly hyped artist). Yes, love is our motto, say Paradisco, and we try to live it every day anew. It's a deliberate decision to go through life like this, says Lea, but there are also difficult moments when you reach your limits. "But we have chosen to be brave, without thinking that in the end it all hurts." The disco has been the scene of many heartache moments. But here we are dealing with Paradisco, the disco next to the disco, the disco that is not a real disco but something on the other side of the street. (For linguists: Para is a Greek prefix and can be translated as "at", "besides" or "beyond".) Let's explain the Paradisco principle using the example of "Two Old Stones", the band's brand new video. The song begins with the ostensibly unsuspicious lyrics "I told my mom about you; I said that you are no good for me.” "That's precisely Paradisco. A smooth surface, but it's got philosophy underneath!" "Is that what a woman does," I ask Lea and Katharina, "to bitch to her mother about the awful boyfriend?” "It's a bad relationship," says Katharina, "so bad that I have to tell my mom." "The song is also meant to be ironic," says Lea, "but if you tell your mom, it clearly has a certain significance." "I told my shrink about you, just didn't go over the tongue well," Katharina points out. Then Lea reaches out to swing big. "The song also has something repetitive, we use this as a stylistic device," she says. “But it's also about standards. Who says a norm is a norm? Is it society and what if you break the norms and change the order? What if you break out? "Now these are bigger questions than I would have guessed from the lyrics," I admit. "That's precisely Paradisco. A smooth surface, but it's got philosophy underneath!" Breaking out, leaving norms and guilt behind, that's what we all struggle with in life, not just Paradisco. Later in the song the lyrics go: "It's time to get away, but I can't". Meanwhile, Paradisco are singing “… and I can” on stage. What led to this change of perspective, I ask Lea later via WhatsApp. "The first times we played this song on stage, I noticed that my view of things had changed for me," she replies. “Life had strengthened me in the meantime and I realized that I definitely have a choice and also the strength to change things. This victimization - but I can’t - didn't suit me anymore. ” In the video for “Two Old Stones” it is actor Andri Schenardi who tries to act as a breakaway. He sits at home being bored - prophetic as Paradisco are, they produced the video even before the current Corona lockdown - and does more and more bizarre things, also with the selfie stick, to keep himself busy. A video entirely in the sense of a critique of today's world, in which self-presentation is the preferred means of communication and sexual fantasies and experimental fetishism have to be lived out alone due to circumstances. But then again: You don't want to be made of plastic and you don’t want to be made of stone, and you even dance with a broken neck, as Paradisco sing in their song "Fantaplast". Where do Paradisco want go with their band and music? In any case, we want to continue, say Lea and Katharina in unison, our project springs from an inner necessity. As a result of their love as a lifestyle, Paradisco also get a lot of love back. They like to cooperate with other arts and artists and are often contacted because of that. "People feel like joining in with us." A feeling that is not foreign to Charlotte Gainsbourg, a musical favorite of Lea and Katharina. In one of her songs she defined the Paradisco principle as follows: "In Paradiscos, we're confined to only pleasure; When you're a flame, you'll burn forever." Whether up or down, the escalator to the eternal jive - as one of the possible travel destinations - goes on and on for Lea Heimann, Katharina Reidy and Paradisco. Listen to "Love is my lifestyle" on Bandcamp here. Souad Massi is "the internationally most successful singer-songwriter of the Arab speaking world". Sandra Arslanian, herself a well respected musician from Beirut , Lebanon ("Sandmoon"), talked with Souad before a recent concert in Antwerp, Belgium It was a stormy Belgian Sunday evening in February, and yet, despite the rough winds and icy rain, the gorgeous concert hall De Roma was full and eagerly waiting for the Algerian-French diva to warm its heart. There she was, as simple and brilliant as ever, graciously holding her guitar, sitting in the middle of a half concave circle – violin and oud to the left, western and eastern rhythm sections to the right. As the tripping sounds of the orient subtly married the pop-folky hooks of the west, carrying her gentle voice to higher spheres of consciousness, Souad Massi unmistakably warmed our hearts and lifted our spirits. Her musicians masterfully followed the inclinations of her pulse, and periodically broke into virtuoso solos. Soon we were all clapping and jiggling on our seats. Belgians and Middle-Easterns alike. We were all one, blending with the music. I even dropped a few trembling tears as she sang “Pays natal” (“Homeland”), unornamented, genuine. “ll n’y avait rien à regretter là-bas…Pourtant j’y pense encore, j’ai un peu mal” (“There was nothing to regret there…However, it hurts a little when I think about it again”). And when I turned my face to look at the Moroccan girl sitting next to me, I noticed that she too was looking for a handkerchief to timidly wipe away the melancholy. I smilingly whispered to her “Matebkiche” (“Don’t cry”), the title of one of Souad Massi’s earlier songs. Folk ballads and more upbeat chaabi, oriental tunes flowed in turn filling the space with sights and sounds of a jasmine scented world of longing and love, owing Souad a much-deserved double standing ovation. Before the show, I had the opportunity to meet with Souad backstage. The interview was a bit delayed due to last minute sound check fine-tunings. Despite time constraints, the encounter was laid-back and we shared some colorful thoughts about womanhood, revolution and life. Here is a freehand transcript of our conversation, complemented with some ad hoc comments. Sandra Arslanian: I know we are a bit late and I know how it feels right before a gig, so this won’t take long. On the other hand, I’m sure that after 30 years of career, you are used to pre-stage stress… Souad Massi: Well, even after all those years, you still feel nervous! (smiles) Beirut - Algiers. We’re in the same kind of socio-political situation, aren’t we? The peaceful protests, the mobilization, the awareness, the youth on the streets demanding a better political system, fighting corruption … It’s true, there is a link between Algiers and Beirut. We are fighting against corruption. But you have other problems as well that we don’t have in Algeria, like multi-confessionalism. However, I must say that I don’t feel this multi-confessional issue when I’m in Beirut. I have friends there of all religions and cultures: Muslims, Christians… I don’t feel the tension. Most of my friends are artists. Art is beyond religion, thankfully. You launched your tour in Beirut… The first gig of my album release, “Oumniya” (“My wish”) was in Lebanon early October 2019, yes. I thought “why not do it in Beirut?”. And then the revolution started on October 17th, a few days after the gig. So you’re the one who organized it… (laughter) I brought it with me from Algeria. But I didn’t do it on purpose. (giggles) Can we call you a socially-committed singer? Among other things, Souad organized a concert in support of the Algerian Hirak in Paris last Spring. I try to be. It’s not easy. But I believe it is important for an artist to have a message to convey. An artist has to awaken people’s consciousness, raise awareness, make things move. It is the role of the painter, the poet, the writer, as well as the intellectual and the journalist. it’s an important role. Stirring people’s consciences… Yes. You are mostly concerned by Human Rights and Women’s Rights. Well, not just by Human Rights and Women’s Rights. I also try to talk about Nature, to defend the environment. Danger is right around the corner. You are thinking about your kids… Souad has 2 daughters, 14 and 8 years old Yes, we have to prepare them to defend themselves. The environmental crisis is acute. Experiencing the revolution from afar, does it hurt? Souad left Algeria in 1999, at the age of 27 when she was invited to perform at the Femmes d'Algerie ("Women of Algeria") festival in Paris. She has been living in France ever since. I am following the events in Algeria on a day to day basis. I try to be present, even from afar by participating in demonstrations in Paris. We don’t have any other choice really. We have to storm the streets, say what we have to say, brandish posters and slogans, sing songs to raise awareness. People need to understand what is going on. There was a beautiful protest today in Paris, but unfortunately, I couldn’t be there since I’m here. You can actually mix pictures of the revolution in Beirut and Algiers, they are so much alike: the youth, the slogans, the posters, the artists, the colors… and the women! Yes, the women! “Once women take to the streets, then you can call it a revolution”. I don’t know who said it, but I totally agree.* It’s great to see women in the Arab world take on this role. Especially in the Arab world! I’m so happy to see the image of the Arab woman change, steering away from the sexy, doll-like figure to the woman wearing jeans, no make-up and defending ideas. It makes me feel proud. *The actual quote is by Lila Benlamri, an Algerian activist who said “When men take to the streets, it is a revolt; when women take to the streets, it is a revolution” Do you think that this flawed image of women is also present in Beirut? It is especially true in Beirut, yes. Beauty is a cult in Lebanon. You worship the body, the physical beauty. Just look around you, on TV, the billboards, it’s everywhere. It is not the case in Algeria. We’re far from the “beauty cult”. Particularly right now, Algerian women are voicing their opinion, they’re present in public spaces, making demands, making their voices heard. There are a lot of strong women in Lebanon as well… Yes, of course. No doubt about that. There is a stigma attached to female artists in the Arab world. And you suffered from it? I read somewhere that in your early twenties in Algeria, you cut your hair and dressed up as a man to be able to continue performing… No, no… I didn’t have to cut my hair for that reason at all. I cut my hair because I wanted to, not because I was compelled to. I was a real tom boy at the time. Nevertheless, it is true that the Algerian society didn’t easily acknowledge or accept differences in opinion or thought. Individual liberties were not respected. We grew up with religious and social constraints, stiff ideas. Women were made to get married and have children. Being an artist – whether an actress, dancer or musician, was not well viewed at all. Thankfully, my parents were more open-minded. However, things are moving in the right direction now, though there is still a lot of work to be done. "Music can make me cry. A single word can touch me." Can we call you a spokesperson-singer? You become a spokesperson in spite of yourself. People project and recognize themselves in you. I’m not bothered to be taken as a point of reference. Such is the role of certain artists. “Spokesperson” in French is “porte-parole”, literally “carrying-words”. Words are important for you. Of course, words are important. For any sensible person, they are! Words carry weight, especially at a certain age. You can say stupid things when you’re 14 or 15, but not at 30, 40 or 50 particularly when you are an artist and you convey ideas. You have to weigh your words carefully. Word over music? Both are important for me. Music can make me cry. A single word can touch me. I attended a poetry reading in Paris recently. I was excited like a little girl, mesmerized by emotion. You don’t like the expression “singer in exile”? I don’t like it because I don’t consider myself as such. My grandfather was in exile, yes. He came to work in France, in difficult conditions, spent years without seeing his wife or his children. This hasn’t been my case at all. I am free, I can travel whenever I want. It is out of respect for those who really suffer from exile, that I refuse this expression. However, had you stayed in Algeria, maybe you would have been less melancholic in your songs? It’s my character to be melancholic. With everything that is happening in the world, it is easy to sound sad. You sing « Pour les voisins d’à côté je ne suis pas une immigrée » (“For the next door neighbors, I am not an immigrant”) in your song « Pays natal » off your latest album “Oumniya”. It’s not my text. It’s by Françoise Mallet-Joris*, a Prix Goncourt recipient. I chose this text because I recognized myself in it. *Who happens to be born in Antwerp, the city where Souad Massi was performing that night. Do you feel a difference when singing your own words vs. words written by others? Souad usually writes in Algerian Arabic or Kabyle. But she sings in Algerian Arabic, Kabyle, French and classical Arabic. Her previous album “El Mutakallimun” (“Master of Words”) was an ode to Arabic, or rather Arabo-Andalusian poetry. I feel a certain pressure when singing words written by others because I want to make justice to the text they wrote. However, I won’t sing it if I don’t recognize myself in it. It definitely has to “sound” like me. Do you write in French? I have given it a try, but I did not pursue it. It didn’t feel natural, and I wasn’t happy with it. There are such good French writers, I let them write in French. Do you consider yourself an Arabic singer? In Algeria, the Kabyle are Kabyle, the Algerians are Algerians… It sounds awkward to me to be called an Arabic singer, because I come from the North of Africa. Why associate myself to the Arab identity per se? I speak Arabic, true. But I am Berber. I am North African. I’d like to be seen as such. So, an Algerian singer? Yes, rather. (smile) A cultural ambassador of Algeria… It’s a beautiful expression. I like it. (big smile) Is there a future for Arab, North African artists if they stay local? It depends. Some can succeed. But socially committed artists won’t be able to succeed in their country due to constraints. Like you… Yes, like me (laughter) Arab News wrote about you: “Internationally most successful singer-songwriter of the Arab-speaking world”. It’s a dream path for all artists of the Arab world, I guess. Souad got signed to a major label immediately after her first performance in France in 1999. She has released 6 albums since, including a string of hit songs (Raoui, Ghir Enta, Le bien et le mal, Houria…) and has toured the world. She won the “Victoire de la Musique” in 2006 and the “Grand prix des musiques du monde” in 2011, and has had the chance to sing duos with such artists as Manu Chao, Cesaria Evora, Francis Cabrel, Florent Pagny… It all happened in a very spontaneous manner. I never really took a step back to think about how it all came to be. I’m still on this path and I don’t ask myself any questions. I guess it’s my life path. I let myself follow the flow. I need time to think about it actually… It’s been 20 years… I know, but I still didn’t take the time to analyze it. You are an inspiration for young artists… Yes, I realize that. When I go to Egypt for instance and I meet young bands who play Rock music… It makes me happy. And I think “oops, now I’ve gotten old”. You yourself have played some heavy Rock when you were young… I was in a Hard Rock group called Atakor… It’s difficult to believe… Well, I didn’t sing any Hard Rock, I only played the guitar. (laughter) . It was at an age when I needed to let out that kind of energy. There were a lot of taboos in Algeria at the time, and playing this kind of music was like braving the taboos. It gave us a kick. You once said “I share my privacy, I lay myself bare” It’s not easy for us singer-songwriters, because we tell the story of our lives. I had a hard time doing this, particularly in the beginning, telling things that are very personal to people I don’t know. With time, I understood and accepted it. I would have had to change jobs had I not*. * She did venture briefly into urbanism/architecture after completing urbanism studies, but dropped it to pursue her career in music. Do you prefer intimate gigs or stadium concerts? I prefer small gigs, in small club venues. I also like beautiful concert halls like the one we’re playing at tonight (De Roma). I already sang in a stadium in Egypt, as part of a festival with other bands. It’s a different experience. You need to adapt yourself. What about being accompanied by a philharmonic orchestra… That’s a different exercise altogether. I’m familiar with classical music because of my formative years playing classical music, like Chopin… Anyways, it’s great: you are in the middle of 40 musicians, in the midst of this “sound”. It’s very emotional. The first time, I was dead scared. But it’s truly magnificent. I don’t know if you’ve had the experience… I’d love to… If it happens one day, you’ll have to make the most of it and really enjoy it. It’s very impressive. “For me, the most important thing is to stay true to myself” You are a genuine singer, you don’t lie… No, I don’t. You also said “I don’t care to make commercial music, I want to do what I love” I don’t make commercial music. If I did, I would have been ultra rich. (laughter) You are a Mother-singer. Your daughter sang with you on “Je veux apprendre” (“I want to learn”) off your album “Oumniya” Yes, I sang with my daughter because when I was recording that song at the studio in Algiers, she was there. My brother who was also there said that it would make sense if she sang on it since the song is about the emancipation of young girls. So we rehearsed the chorus, and recorded her singing it. I loved it. We immortalized the moment. And with this interview, albeit on a different level, we immortalized our conversation. Thank you Souad. Sandra Arslanian is the leader of Beirut's indie pop/rock band Sandmoon. Sandmoon's latest track and video is "Angels". A next Sandmoon album will be released soon. After 15 seconds into Murur al-Kiram, Kinematik’s new album to be released on February 28, you already know that you are in for something exceptional. There is no way that an album can start with such a strong drum beat and then end up being a weak recording. Starting an album on a drum beat only also means one thing: Kinematik have thought about this album carefully; they know what they are doing and nothing is random. Murur al-Kiram is a real album, not a collection of songs that were “just ready” to be released. Kinematik may not know it, and they may not even care about it, but their album exactly follows the playbook of “how to approach album track order in the digital age”: start strong - tell a story - don’t worry about shuffling. “What is the story of Murur al-Kiram?,” I ask Kinematik when I meet them in Beirut at the beginning of 2020. Anthony Sahyoun, Rudy Ghafari and Akram Hajj all sip beers when talking to me in the basement of Riwaq, one of their usual hangout places. Anthony is the most outspoken member of the band, so he goes first, as often. “Our first album was a compilation of everything that we were able to do at that time,” he says. “The artistic decisions only had to do with our capabilities as musicians. It was like, ok, this is what we can express, this is what we know how to express, so let’s put it on record.” Rudy Ghafari adds his version of how the second album is different from the first one: “You can say that the first album was one big happy accident. Whereas the second album is a series of mini accidents.” Murur al-Kiram is indeed very different from Ala’, Kinematik’s first album. It contains less guitars and more synthesizers and is driven throughout the album by the multifaceted double drumming of Akram Hajj and Teddy Tawil (who is not an official member of Kinematik, but collaborates with Anthony on another exciting project, May Bardé). If I had to come up with an abstract of the underlying story of Murur al-Kiram, it would go like this: Murur al-Kiram starts with an optimistic, powerful beat which could be a metaphor for young boys enjoying a happy youth somewhere in the fresh air of the Lebanese mountains. Soon the drum beats are followed by synthesizer sounds, the musical expression of fantasy landscapes and future universes of which an innocent adolescent in Lebanon can only dream. "Our presence here is like Murur al-Kiram, like en passant. We are here, but they don't care." With “W Kaza”, the ninth song of the album, the Lebanese reality brutally kicks in. The song is pure destruction and exhaustion, like banging your fists in protest against the gate of a palace (or the building of a corrupt government, if we want to stay in the Lebanese context) that will remain closed, however strong you bang. Murur al-Kiram ends with “Roza” - the most “churchy” of our new songs, as Anthony explains - because after all, when everything in Lebanon is said and gone, religion will stay to soothe the ones that have not found their worldly redemption yet. Since October 17, 2019, the Lebanese again try to change their political system and in fact the entire society, having come out in masses to the squares and streets to protest against the ruling class, the corruption and the sectarian system that suffocates the country and its people. The album's title Murur al-Kiram, which can be freely translated as “the privileged are passing by”, is a sarcastic reference to how Kinematik feel about their situation as Lebanese citizens (and this even before the thawra, as the album was recorded prior to October 2019). Like many other Lebanese, the members of Kinematik sense that their presence in the country is not validated in any way. “It’s like a what-the-fuck-am-I-doing-here kind of thing,” says Anthony. “Our vote, our life has no value. We are stuck with the status quo, our presence here is like Murur al-Kiram, like en passant. We are here, but they don’t care.” “When you listen to W Kaza,” says Rudy, “then remember all your visits to Beirut. That’s the track that expresses most how we feel about everything.” Anthony agrees. “Track nine is literal exhaustion, that’s what it is. It’s exhaustion and defeat and it comes from the drumming. In this song we have this really heavy drum sound and this really heavy bass line. In the studio Akram was slowing down because he got exhausted playing it. And your impulse as a musician would be to pick up the tempo again. But we said no, don’t pick it up. Just get exhausted and let it slow down all the way.” Slow down until all your black thoughts have vanished. What happened to Lebanese band Mashrou’ Leila last year was a big shock for Kinematik. (Mashrou’ Leila were banned from playing at the Byblos festival in Lebanon in 2019. They became the victims of a political power game that was played out on the band’s back, with people leading an online campaign against them because of one or two lines within their lyrics that made references to religion. Of course the fact that Mashrou’ Leila’s lead singer is gay didn’t help their cause either.) “When we last met,” I tell the band, “we talked about your black thoughts. Your ideas about a lot of things are blacker than Mashrou’ Leila’s, but people don’t realize it because your songs have no words.” “Actually my mother said this to me when the Mashrou’ Leila thing happened,” Rudy says. “I was arguing with my mother. She told me, Rudy, your music is actually worse (than Mashrou’ Leila). When Mashrou’ Leila use a reference from the bible, people go crazy. Put words to your music and people would be very pissed off. It’s way worse.” So far Kinematik haven’t put words to their music, because it never felt organic and natural. “If we did,” says Akram, “I think that I would like to say something very melancholic and sad.” “True. there is sadness in our music,” Rudy comments. “But actually, and put the music aside, we are happy people. Despite the depressions we go through. And despite the anger.” Yes, the general tone of Murur al-Kiram is melancholic, however the album is not as gloomy as it might seem when reading these lines. There is also much beauty and hope in Kinematik's music. At the end of the day, Anthony, Rudy and Akram want to stay in Lebanon, they don't intend to leave the country as many Lebanese do. When Lebanese sound defeatist in their talk, it's often meant to be funny, not depressing. To make an album great, it’s not only the music that counts, but also the pauses and the transitions between the different parts of the recording. Judging by this, Kinematik have done an outstanding job with Murur al-Kiram. As Anthony keeps repeating during the interview: the band tried to be as honest and as hard on themselves as they possibly could when recording the album. The material was reworked and reworked until it felt right. There weren’t any hacks and cheap tricks allowed this time around. The composing of Murur al-Kiram was like “you have an idea, you try to abuse the idea,” Anthony explains. “And if the idea survives all of your abuses, then it was a good idea and you keep it.” The result is Murur al-Kiram. It is an album full of ideas that have survived. It is an album made by people who have survived. It is an album that won’t just pass by unnoticed. photos and cover art by Joe Saade “If someone fine, dignified, prolific, brilliant is born in the future; if someone unique and unrepeatable is born, a Bach, a Rembrandt, then he will win people over, charm and seduce them.” Witold Gombrowicz, the controversial Polish author, was in fundamental opposition to most things, but he had never lost hope for the art and the artist. “Are you the person that Gombrowicz describes?,” I ask Hania Rani when I interview her before her concert in Bern in December 2019. “Are you the new Bach?” She laughs. “I would never put myself in this group of people. Gombrowicz is an excellent observer of life and of the meaning of life. But he also sees the irony in it.” Hania Rani is a pianist, composer and musical arranger from Poland. This year is her first with international fame, after having released her debut album “Esja” in April of 2019. The album is included in many best-of lists of 2019. On her debut, Hania Rani performs ten compositions for solo piano, each one a gem of a new musical style that has become very popular recently, usually branded as neo-classical. Her music has brought Hania Rani to numerous venues in Europe this year, to Aarhus in Denmark for instance, where she played an acoustic set for a handful of people in a jazz club, to the Netherlands, where she performed in a church, but also to Japan, where she played in a big hall in front of over 1000 people. “How is your new life on the tour?,” I ask Hania Rani. “How do you stay healthy and in good spirits while traveling so extensively?” “In the beginning it wasn’t easy,” she says. “But because it is a job like any other job, I must stay focused. I have to repeat the same show every day and give a lot to the people every evening. It was difficult in the beginning, but I got used to it because I really like to perform. It is something that lifts me up.” “Don’t you get bored after a while, playing the same show every evening?” “Well, it’s always changing,” Hania Rani replies, “because we play in different cities and different venues. I also try to take my time before and after the concert, to get to know the places and the people for whom I am playing. I want to establish a connection, something that I can remember later on. It’s my first big tour and I want to fully experience and enjoy it.” “Esja”, Hania Rani’s album, was partly recorded in Reykjavik, Iceland’s capital, and is named after a nearby mountain. The music on “Esja” is sublime and laid back in a very delicate way, with Hania Rani carefully finding her way through the songs just as my car does when I drive to the office through the falling snow a few days before the concert (while playing her music). One of the trademarks of neo-classical piano music is to showcase the piano as an organic and mechanical body. When listening to songs like Biesy, Luka and Glass, one hears Hania Rani press the keys and play the melodies of course, but one also hears a piano at work, creaking and breathing like a wooden boat in heavy sea. The first thing that strikes me when meeting Hania Rani in person and seeing her in concert: she is profoundly relaxed and unaffected by the hustle and bustle of a life on the road. She is late for the soundcheck and we don’t have time to do the interview? No problem, she says, let’s talk over dinner, just minutes before she goes on stage. The audience in Bern is very mindful and ready to receive. Couples kiss when Hania Rani plays and heads turn around in contempt when someone struggles to silently open a plastic wrapper. This is a liturgy of divine sound, for Christ’s sake: who is the heretic in the room? Hania Rani links two, three songs and plays for 15 minutes in one go. At the end of such a run nobody dares to applaud until they are 100% sure that this is really the end. No one wants to kill the sublimity of the moment, and uncover himself as hopelessly ignorant, by clapping when clapping is not yet due. We all know that if someone speaks softly, people listen better. With Hania Rani and her music it is the same. "For me, what I do is punk." But who is Hania Rani really? For her Instagram profile she uses another Gombrowicz quote. “Je suis un humoriste, un plaisantin, je suis un acrobate et un provocateur”, it reads. “I like this quote,” Hania Rani tells me, “because it says a little bit how I feel as an artist. I am an entertainer, that’s my job.” And she repeats: “I’m an entertainer.” However Gombrowicz’s original quote has a second, more subversive part - “je suis cirque, lyrisme, poésie, horreur, bagarre (a brawl), jeu, que voulez-vous de plus?”. Witold Gombrowicz was called a proto punk, a punk before punk was born, for swimming against the currents of his time. Hania Rani doesn’t look punkish at all, but “I like to be a punk in my mind,” she says, when I ask her about it. “For me, what I do is punk. I used to play classical music. Everything I do now is a total rebellion.” Hania Rani’s second album has already been recorded and mixed and will be out sometimes in 2020. The album will be different than “Esja” and Rani risks to disappoint some of her newfound fans of 2019 which slightly worries her. There will be a couple of solo piano songs - of course - but the rest of the album will have much more instruments as it was recorded with a small band. Already in Bern Hania Rani surprised some in the audience when she was singing (she is probably the best piano player among all the singers in the world). When she announced on Facebook that mixing the new album was completed, she also noted that “Nothing has changed. Everything has changed”. Hania Rani likes to tease her followers by publishing enigmatic messages online. “On the one hand everything has changed in my life because of ‘Esja’,” Hania Rani explains. “I am now in a totally different place and I am doing totally different things. I also have many great offers to collaborate. On the other hand I think that I am quite the same as before my success and I try to lead my life the same way.” “So Hania Rani is still Hanna Raniszewska?” “Yes!” (photo credits:: Aleksandra Pawlowska, Nat Kontraktewicz,, Marcin Leszczynski..) His numbers on Spotify are very modest. When I talk to Andrea Kaiser, who is just Kaiser to most people, I tell him that he has ten monthly listeners on Spotify (and one of them is me). That’s awesome, Kaiser replies, I’d love to send everyone of them a bouquet of flowers. Catering to the masses has never been Kaiser’s goal when making music. In fact he would change his musical style immediately should this style ever become mainstream and enjoy commercial success. In October of 2019, one month after the release of his latest album Songs of No Return, this is not a particular risk. Kaiser is the founder and at present the only member of Dnepr, a band that started its career deep down in Bern’s underground music scene of the 1980ies and has not moved up considerably since then. (And yes, there used to be an underground scene in Switzerland.) Do you still talk about the 1980ies?, I ask Kaiser. Sure, he says, when I’m asked. Kaiser’s memories of the starting years of his career are still very much vivid. Between 1987 and 1995 he had released a bunch of six records and he still remembers every detail about each of these songs. Dnepr combined Kaiser’s heavy guitar - sometimes rhythmic, sometimes gloomy and plaintive - with elements from post punk, prog rock and new wave. The intention was always to be provocative, with a distinct nihilistic attitude, and play with political buzzwords in a period when the cold war was still fully on. Dnepr is a great motorbike brand from Ukraine, Kaiser tells me, and I wanted a name for my band with an eastern, communist touch. Dnepr’s first album was called Hymn of Nihilon and it was inspired by Alan Sillitoe’s novel “Travels in Nihilon” where a group of people is sent to the country of Nihilon to collect information for a new travel guide. In Nihilon honesty is outlawed, drunk driving is mandatory and nihilism reigns supreme. TV and radio news are announced with “Here are the lies!”. These are just the kind of subversive ideas that Kaiser loves. All of Dnepr’s albums were recorded in Nihilitz Studios at Ulaanbaatar; Nihilitz being the drink that Nihilon’s citizens usually drink and Ulaanbaatar the capital of Mongolia, a former hidden treasure of a communist-ruled country. In reality Kaiser’s studio is just a small room in the basement of his apartment in Bern, just big enough for him and his guitar. Kaiser has never traveled to Ulaanbaatar. While Dnepr’s music is purely instrumental now, there were lyrics in the first period of Dnepr. Have you lost your inspiration for words?, I ask Kaiser. Not at all, he replies, I never had troubles expressing myself. It’s just that I find it more challenging these days, but also more of a thrill, to produce music without lyrics. With lyrics, you can repeat them over and over again and you have a song. Without lyrics, your compositions need to be constructed differently in order to keep the song going and the audience listening. Dnepr has always been avant-garde. For “Figures in a Landscape” from Hellhome, Dnepr’s 1993 release, a computer generated voice spoke words that had been fed to the computer by Kaiser (by profession, Kaiser is a software engineer). “Deus Ex Machina” and “The Nile Song” (both from Vandalism, 1991) are similar adventures in sound. Other songs on Vandalism - “The definitive Birth, the ultimate Life and the absolute Death”, as well as “Come back (I want to kick into your ass)”- definitely excel through their innovative titles, one profound and one more than subtly funny. By comparison, The Empire Strikes Back from 1990 is a rather conventional album, with music that can be qualified as industrial heavy metal based on piercing guitar riffs. What did stop you from becoming as big as Metallica?, I ask Kaiser, because you certainly had the talent. Well, I don’t know, says Kaiser, always the humble man. It also has to do with luck. You need to be young to start such a career, to make it big. Music consumers today are kids and teenagers. They need to be able to identify with you. If you are 30 plus, that’s almost impossible. Add to this Kaiser’s eternal refusal to compromise on his music and you know why Dnepr is not a household name in the charts. Fast forward 23 years to the beginning of 2018. The world has not heard a lot from Dnepr, or Kaiser, since 1995, certainly not in the form of an album. What happened, Kaiser? Kaiser doesn’t want to talk about these years of near retirement, except in private mode. But then, slowly slowly, he crawled back to life and music and reactivated Nihilitz Studios. Songs of No Return is promoted as your comeback album, I mention to Kaiser, but actually you have already released The Nine Gates two years ago. I am happy that you make me talk about it, he replies, so for the first time I get to explain what is the story behind the nine gates. "Maybe I am infected by a software virus that damages my operating system." The first connotation with this album title are the nine gates that lead to hell, Kaiser illuminates me. But I also see this as the nine month of pregnancy and thus you arrive at an equation life = hell. Most people find life quite ok, because they have a mechanism built in that helps them to suppress any fear or doubt they may have. Without this mechanism, we couldn’t exist. For myself, this mechanism is slowly wearing off, maybe because I am infected by a software virus that damages my operating system. George Orwell helped me to see that I am not alone in this: “any life when viewed from the inside is simply a series of defeats”. How come The Nine Gates has twelve tracks? The three extra tracks are the afterbirth. It happens quite often. I have a concept, I write tracks, and when I’m done, more stuff needs to get out. With Song of No Return, Dnepr and Kaiser are really back. The album consists of twelve songs that Kaiser wrote and recorded all by himself. I am inspired to work alone at the moment, says Kaiser, it’s efficient, no discussions, you don’t have to convince anyone. Would you consider yourself a loner, a bit of an oddball?, I challenge Kaiser. Yes, he says, to a certain extent. However I am not antisocial. The Open Enso Talks: one hour with Kaiser a/k/a Dnepr (language: Swiss German) The new Dnepr album is literature turned into music. Kaiser likes to read - long, difficult reads, mostly from dead authors - and he knows his books well. “Zettels Traum” is inspired by the monumental work of the same title by Arno Schmidt (my song is not a musical abstract of the book; it’s the soundtrack of a dream with breaks and surprising twists, Kaiser says); “Venaska” is a main character in Alfred Döblin’s utopian novel “Berge, Meere und Giganten”, polygamous and bisexual (the book is about contrasts. It’s a dystopia with a woman, a goddess of love, who is called Venaska. I tried to compose a song that is oscillating between the ugly and the beautiful).

Kaiser is a nerd for sound. At any time of the day he may feel inspired to go down to the basement, in his studio, and work on a track. All night long, if needed. Once he dreamt of a counterpart to a leitmotiv he had composed earlier. When he woke up, he immediately ran downstairs, naked as he was, strapped on his guitar and recorded the idea. Are you nerdy with guitars as well?, I ask Kaiser. I am not a collector, he says, I only own two guitars (two handmade Gordon Smith guitars, made in UK). In the end it’s the effect pedals and the amplifiers that create the sound. If I go to a concert and the guitarist hauls a rack with five guitars onto the stage, I know that I am in the wrong place. Dnepr have never played a lot of concerts, not even in their primetime in the 1980ies and 1990ies. In 2018 Kaiser played one set in the knight’s hall of an old castle near Bern. This year, there were the album launch in September and another gig in November. And that’s it. I like to play loud, Kaiser explains, really loud. Preferably at 120 decibels. In most places that’s not possible. But I can’t trim down. Playing my music at 93 decibels? Even whistling is louder! Already Kaiser has ideas for a next album. Is he recording? Not yet, he says. I am all about re-inventing myself. But when I start something new, I find my old music crappy. I am not yet ready to ditch Songs of No Return. That’s why I stick with it for the time being. I don’t even remember how I came up with the last question for Kaiser, but I must have been touched by something when listening to Dnepr’s albums: does he believe in love? Despite of his wary attitude towards society and his reluctance to comply with the masses, despite of all the utopian landscapes and the dystopian soundscapes that he creates: everything in Kaiser’s music is love. It’s a love that he gives and a love that he yearns to receive, forever carried and supported by the big waves of hope - hope for humankind, hope for a more human society - emanating from the strings of his guitar in Nihilitz Studios at Ulaanbaatar. It is because of love why we are on this planet, Kaiser answers. Without love we wouldn’t do anything, without love we wouldn’t make music. We would simply squat on the ground and pick our noses. Dnepr will perform at Les Amis/Wohnzimmer in Bern, Switzerland, on November 14, 2019. Be there (and have your earplugs handy)! My good friend Georgy Flouty was very excited. “You’ve got to listen to this,” he whatsapped me in August. “It’s the best album I’ve heard in the last five years, a French trio in their early twenties.” Georgy is not just anybody. He is a very talented musician who plays the guitar in a number of Lebanese bands, among them KOZO and Sandmoon. I immediately kicked off Spotify. “I like what I hear, very much so,” I replied to Georgy soon afterwards. “And you know what? They will play in Zurich on October 9. However there will be Deafhaven the same evening.” “They are insane live,” Georgy texted back (although he had never seen Lysistrata in concert, only some YouTube videos), “It reminds me of the first time I heard Spiderland (Slint’s legendary post-rock album). The same rush of heavy emotions.” And then: “Deafhaven can wait!” It’s October 9, I am in Zurich heading for Dynamo, a small club near the Limmat river. Lysistrata will perform here this evening, opening for Decibelles, a French band as well. Originally Lysistrata were scheduled to play at another venue, but the concert was canceled because of low pre-sales. Luckily Lysistrata were able to convince Decibelles to take them onboard for their gig. There is a lot of competition in town tonight. Lysistrata are a household name in France but even the best bands have troubles finding their audience if no one knows them, like in Zurich. In a few days, Lysistrata's second album “Breathe In/Out” will be released. Meeting the band proves simple. Ben (drums), Théo (guitar) and Max (bass) are very accessible and easygoing. We sit down on the edge of the stage and start talking. Max is holding my mobile phone like a microphone to better record his and his colleagues voices. “How did you approach writing and recording a follow-up album when your first album was so successful?,” I ask the band. “You can only disappoint.” Ben is the first to answer. “We didn’t ask ourselves too many questions. We had all these riffs and stuff so we kind of assembled them. Our first album was a bunch of songs we had played for a long time and we wanted to get them on a record. For the second album, we were getting tired of playing the same songs all the time. We needed to produce some new stuff.” “Artistically we are totally free,” Max adds. “There is no pressure from the label, they are just interested to hear the final result.” When reading about Lysistrata one can clearly see that journalists struggle to define the band’s musical style. What is it what they are doing? Something between noise-rock, emo, math-rock and post-hardcore are the stamps that most articles try to put on Lysistrata, each article copying a previous one. The band’s influences are quoted to range from Sonic Youth and Nirvana to Fugazi and At The Drive In, a band from El Paso, Texas. “We have tons of influences,” says the band. “We listen to a lot of bands from the 1990ies, but also more modern stuff. However nothing in particular.” In an attempt meant to be half serious but also to make a joke, Lysistrata call themselves “Post-Everything”. All we do is post, they say, everything has already been played and done before, in one way or another. “If you are indeed Post-Everything then you are in fact Pre-What?,” I want to know. “What can happen to Lysistrata in the future?” Ben has an idea: “Maybe Post-Everything is actually Pre-Nothing. Maybe even Pre-Everything and Nothing.” Despite their very young age - and perhaps precisely because of that - Lysistrata have a lot of self-confidence. They are certainly not bothered with finding a label and a drawer for their brand of music. It’s just their way of rock ’n’ roll. When I listened to Lysistrata to prepare for the interview I did it in the gym most of the time. Their energetic, in-your-face rock songs make you go faster on the treadmill and lift heavier weights. What is Georgy’s take on Lysistrata second album? Already back in August Georgy had his doubts. “Their new album comes out on October 18,” he said. “ I hope they can keep the bar up high (which is not doable in my opinion).” “What caught my attention in their debut album ‘The Thread’,” Georgy later told me, “is the balance that Lysistrata created between the different genres of music I grew up listening to. The album smoothly shifts from harsh noise to emo-like math-rock, with beautifully placed and timed chords and transitions that kept me on the edge of my seat. It’s chaotic and immature in the best of ways. As for the second album, I feel that they tried too hard to be more mature. It’s not as fun and flowy as their debut.” “We have transposed our setup from the rehearsal room onto the stage.” For my part I had much fun listening to Lysistrata’s second album and never got bored doing so. On stage Lysistrata are a powerhouse of their own. Too bad the concrete walls of the Dynamo club are a graveyard for any nuanced sound. The band’s energy is extremely engaging and their “singing à trois” makes them anything but choirboys. However what distinguishes Lysistrata from the rest of the rock pack are their long instrumental parts. Guitar, bass and drums are super tight and intertwined and at the end of a long dash to rock heaven and back, the difference between everything and nothing is all but blurred in my head. Lysistrata being so overwhelming on stage is also fueled by the way they set up the band when playing live. It is the same triangle formation that we know from FC Liverpool’s “trio infernal” of strikers Sadio Mané (let's say that's Max), Roberto Firmino (Ben) and Mohamed Salah (Théo). “On stage you are like locked in,” I ask the band. “What is going on inside the zone?” Ben again has the one-liner that explains it all. “We have transposed our setup from the rehearsal room onto the stage.” Théo and Max continue: “to truly play our music we need to look at each other often. It shows that we like a lot what we do. It has always been like that. We are like in a bulb. While conventional groups front the audience, we slightly turn to each other. Ultimately, the music happens between the musicians.” Lysistrata seem to be gone for a never ending world tour, playing gig after gig. Just last weekend they have been invited to the Blackwoodstock Festival in Nouvelle Calédonie (one of France’s overseas territories in the Pacific Ocean) and flew 30 hours to get there. They also have performed in Malaysia, Vietnam and China. Have they ever been threatened by a sex strike by their girlfriends because they spend too much time on the road? After all, Lysistrata is the historical figure that organized the sex strike in ancient Athens to stop the wars between Greece and Sparta. The band is laughing. “So far all is quiet on that front.” Lucky them, lucky us. The Lysistrata-show will go on. Very soon and very surely in a location near you. An architect walks into a bar… That’s how I intended to begin this article. But searching the internet for jokes starting with this phrase didn’t yield any satisfying results. Certainly not funny ones. Are architects too busy to go to bars? Or are they not funny? For my part I had much fun talking to the musicians of KOZO at Beirut’s Tunefork Studios between rehearsal sessions. And this despite the fact that, or maybe because, three of the five members of the band are architects. KOZO are funny but also very smart people. It may have been my smartest interview ever. A talk with KOZO makes you consult Wikipedia more often than an incontinent person rushes to the toilet in one day. The history of KOZO told in one sentence: they absorbed Filter Happier (another great Lebanese band). In reality KOZO is the result of a lot of courage. Andrew Georges (guitar) and Charbel Abou Chakra (bass) were playing in a band doing Sigur Ròs covers at the time. They were looking for a competent drummer to complement the band. Filter Happier on the other hand were a band “in suspension”; their singer had moved to France and their bassist to the USA. Andrew saw Filter Happier play, liked what he saw and mustered up the courage to talk to them (architects are also shy people). Elie el Khoury (drums) quickly agreed to join Andrew’s band and so did eventually Georgy Flouty and Camille Cabbebé (both guitars, and the two non-architects in KOZO). “I was particularly scared to talk to Georgy,” says Andrew during the interview. “He is a pro, he was in bands, he has been on tour in Europe and has this intimidating aura.” (Georgy: “What?”) Architects. Music. Enter Japan. On September 7, 2019, KOZO will launch their debut album “Tokyo Metabolist Syndrome” at the SoundsGood Music Festival in Rayfoun and it’s an unusual album. KOZO may not call it that way but it’s a concept album celebrating metabolism, a post-war Japanese architectural movement, and comparing it to the state of architecture in Lebanon. “Actually, I don’t like the term concept albums,” Andrew says. “it reminds me of herbal, cheesy records from the 1970s.” Charbel and Andrew are both architecture buffs who post regularly about their passion on Facebook. For the rest of us it’s time for a crash course in metabolism. Metabolism was a movement that explored methods of large-scale reconstruction for Japan’s cities severely damaged by the war. Between the 1950s and 1970s, Metabolists like Fumihiko Maki, Kenzo Tange and Kisho Kurokawa emphasized the need for Japanese architects to emulate organic systems in their designs for urban megastructures, highlighting how metabolisms in complex organisms work to maintain living cells (I told you that KOZO were a smart band). In short, buildings and structures (and interestingly enough KOZO means structure in Japanese language) were seen as living bodies consisting of self-sustaining and self-adapting modules. Now how does the music of KOZO relate to the architecture of metabolism? “I tell you how it started,” says Elie. “We started covering songs from bands we liked and from that we figured out our own sound. It was and still is an entire process.” Andrew jumps in: “the idea of architecture in music is about sticking to a process. And accepting the little inconsistencies that happen when you stick to a process. You get those random results at times. We abuse these and make them part of our music.." The music of KOZO is heavy on drums, bass and guitars and their songs often don’t fit the usual radio format. They take their time exploring the landscapes and horizons that lie ahead of them. In exemplary math rock tradition it is music made by nerds that doesn’t sound too nerdy after all. “I like when things don’t sound like you expect them to,” Andrew explains. “With KOZO, it’s my doom metal guitar versus their (Camille’s and Georgy’s) sparkly dream pop riffs. And it works!” Performing the music live feels very physical, Elie adds. “For all of us it is a mental exercise because we use a lot of odd time signatures.” The band admits that they tend to overthink their music when in the studio. “But when we play it live,” says Elie, “that’s when I feel that we really unleash.” “There is a lot of freedom when playing with KOZO. I am not restricted to anything."

Many bands play songs with a “verse - chorus - verse - chorus” schema. KOZO aim to break this established pattern in order to maneuver out of their comfort zone. However there is a side effect: with a regular song you have a place to land on with the song. With songs made by KOZO this comfortable landing spot is gone, for both the band and the listeners. “For me there is a lot of freedom when playing with KOZO,” says Camille. “I am not restricted to anything and I never strum an actual chord. I come in for a bit and then I go out again.”

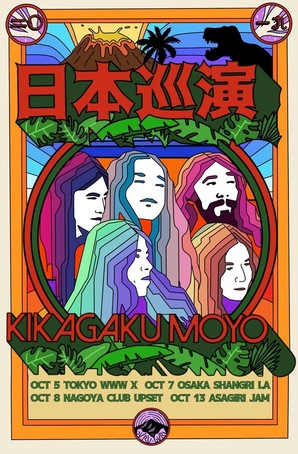

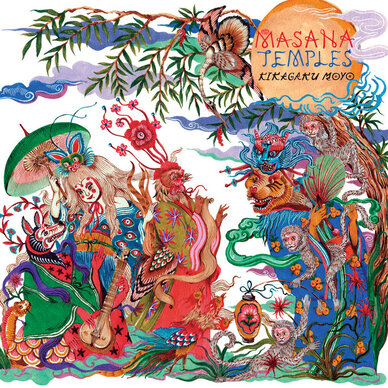

So how do the listeners react to KOZO’s music? They don’t know when to clap, says Georgy, jokingly. When performing in the north of Lebanon as part of a school event, the kids left the concert but the parents stayed. The band has had great feedback from people whose demographics they didn’t have on their radar. And Camille reveals one of the best kept secrets about KOZO: when they sing (and on many songs they don’t), they sing in Arabic! “For a long time,” Camille tells me, “all my friends thought that we sing in Japanese. Because they looked at the songs titles and assumed that the lyrics would be in Japanese." The song titles are indeed very Japanese and read like a history of the metabolist movement. “Tange” (referring to Kenzo Tange, one of the founders of metabolism), “Osaka 70” (the world exposition in 1970 for which Tange had planned the site), “Capsule Tower” (the icon of metabolism in the Ginza district of Tokyo) and “Tokyo Bay Plan” (Tange’s proposal for extending Tokyo into Tokyo Bay): what is this infatuation that KOZO have with Japan? They have never visited the country and they don’t even speak Japanese (but according to Soundcloud we now have fans in Japan, says Georgy). Andrew takes a deep breath. “As architects,” he explains, “we became enamoured with the concept of metabolist architecture. And then we realized what Japan did after the war and what we did in Lebanon. We sadly ignored whatever potential was present at a certain time and let it slip away. KOZO’s music is about implying our naive understanding of this land - Japan - that is literally far away and dreaming of an architecture for our land that has the same weight as the metabolists had for Japan. People who built futures in the now distant past that we are imagining for our own future, in perhaps the most childish way.” If you have 6:44 minutes to truly understand what Andrew Georges means, then listen to “Tokyo Bay Plan”, the last song on KOZO’s album. If you have only twenty seconds to spare, then fast forward to the end of the same song and focus on Elie firing a final salvo on the drums eight seconds before the end. You will know. That’s Lebanon, that’s the Orient, that’s the land of damnation and salvation, in a musical nutshell. KOZO’s music, although mostly instrumental and without words, is more political than the music of many bands that have been driven to the gallows lately. Lebanese are a people suffering from Stockholm syndrome: they have been conditioned to be in love with their worst enemy, themselves. KOZO are aware of this but don’t know better than to hang in there. “We are a Beirut-based band,” they say, “we couldn’t write our songs outside Beirut.” This was certainly true for the first album. Yalla guys, you now are ready to leave the cocoon. Come to Europe, go to Japan, play concerts, compose new songs, the world is yours. Japanese love surprises. KOZO would definitely be one of them. Yesterday evening in Oslo, tonight in Bern, tomorrow afternoon playing at a festival on an alp in the Valais: Kikagaku Moyo don’t take it easy to bring their music to the people. "Last night we did not sleep at all," Go Kurosawa tells me before the concert at ISC in Bern, Switzerland. “We finished the concert in Oslo at 2am, at 4am we were back at the hotel and two hours later we had to leave for the airport.” "What do you do to ease the stress when touring? Working out?,” I ask Go. "No, I'm the drummer”, he replies, "that's already pretty physical. I relax when I play on stage. And when I'm really tired I tell myself that I’m extremely lucky to be able to do what I love to do." Kikagaku Moyo have been around since 2012 when the band started out busking on the streets of Tokyo. Their last and best album so far, "Masana Temples", is from 2018, recorded and produced in Portugal. Besides Go, the band consists of his brother Ryu on sitar, Tomo Katsurada on guitar and all sorts of percussion instruments, Daoud Popal on guitar and Kotsu Guy on bass. Kikagaku Moyo play psychedelic music: they like to improvise and take their time for long songs. Psychedelic music dates back to a time in the 1960s when artists believed that drugs would make their music sound better. Psychedelic drugs such as LSD led to an increased consciousness among consumers, which then had an effect on the music that was composed and played under the influence of these drugs. On the other hand, this music also had the effect of deepening and expanding the experience of the drugs. It was the classic example of a mutual leverage that was not always understood by outsiders. "Can you play psychedelic music without drugs?”, I ask Go. "I think so”, he replies. "In the past I also took drugs, but not anymore. It's about experimenting with your consciousness. You can achieve the desired state without drugs. Sure, the drugs have played an important role in the history of psychedelic music, but reducing everything to drugs would be too much of a shortcut. Psychedelic is like a philosophy: it's also about the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, it's about literature and also about fashion.” (Kikagaku Moyo are indeed a band with style and undoubtedly look good. GQ recently hyped them as “they might be the best-dressed band of the decade.") "Everything is just music and there is no ‘me’ anymore.” The desired mental state, however, can not be reached through two-minute songs. The true trip only begins when the music draws longer. Kikagaku Moyo then try to focus five individuals on one thing, to create something unique under this burning glass. This is a kind of collective meditation and as if in a trance the band shoves forward with their music. "For me as a drummer, this condition is relatively easy to achieve," says Go. "I'm sitting in the back of the stage, in the dark, and can plunge into my own zone, away from the audience. I stop thinking and my arms and hands work automatically. Everything is just music and there is no ‘me’ anymore.” Right from the start of the concert the audience falls into an "instant trance". A repetitive bass line, strumming guitars, Go who sits at the drums and sings: The tense drowsiness of the band goes well with the sleepwalking spirituality of their music. A few minutes into the first song the heads of the listeners already bob dangerously. Kikagaku Moyo are constantly looking for a unification in sound until a groovy bassline sets in and leads the band out of their self-imposed impasse. For some songs the drums are left aside. Tomo has all sorts of sound gadgets in his repertoire - triangle, gongs, cowbells - and Go tries his hand at the flute. These are special effects almost like in filmmaking. My imagination goes into overdrive as well with Kikagaku Moyo’s brand of music. And this not only in a concert setting but already when I listen to their album. Let’s take "Dripping Sun”, the second song from the Masana Temples album. It starts out as a Sergio-Leone spaghetti western and then quickly merges into a 1970s cop movie (it could also be something by Quentin Tarantino, "Jackie Brown" maybe). Later I see a car chase (or even a helicopter overflight?), just before the songs fades quietly back into suburban Japan, to people who wait for the bus while enjoying the sun (if they had the leisure to do so). The city pop of Tatsuro Yamashita trickles down their ears through their Sony walkmen. However the situation is more serious than one thinks. The guitars are racing in California and the last dolphins are dancing far out in the sea. At the end of “Dripping Sun” we are back in the police film which is slowly heading towards a showdown. The hero thinks back to Japan one last time. Then the sun goes down for him as well. For once in Bern, Guillaume Hoarau, the star striker of the local football club, is not the favorite player of the masses. Tonight it's Daoud Popal, Kikagaku Moyo’s guitarist. His fuzz guitar keeps cutting deep furrows in the feel-good-field of non-violent music that his colleagues till with a smile. He is assisted by Ryu Kurosawa's sitar. "The sitar is really a special instrument, it could almost replace an entire band," says Go Kurosawa. "There used to be quite a few bands with sitars. But we want the sitar not to sound like Indian kitsch, but modern. That's why we use the sitar like a guitar, with amplifiers and effect pedals. I assume that Greta Thunberg listens to a lot of psychedelic music. If not, she should start to do so, to give her message even more depth. Mindfulness - towards fellow human beings, towards nature, towards oneself - is contemporary. In this sense, psychedelic music is also contemporary. The message of Kikagaku Moyo may be more necessary today than it was then, when this music had its big bang. It goes beyond a mere "Peace and Love". It means, in the truest sense of the Greek origin of psychedelic, to let the soul manifest itself and to develop the potential of the human mind further. Then we will be able to again give little things the appreciation they deserve. This may seem like little. But we have to start somewhere. |

EditorKurt is based in Bern and Beirut is his second home. Always looking for that special angle, he digs deep into people, their stories and creations, with a sweet spot for music. Archives

September 2020

Categories

All

I'd love to discover you. Share your creations here.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed