Menu

|

An architect walks into a bar… That’s how I intended to begin this article. But searching the internet for jokes starting with this phrase didn’t yield any satisfying results. Certainly not funny ones. Are architects too busy to go to bars? Or are they not funny? For my part I had much fun talking to the musicians of KOZO at Beirut’s Tunefork Studios between rehearsal sessions. And this despite the fact that, or maybe because, three of the five members of the band are architects. KOZO are funny but also very smart people. It may have been my smartest interview ever. A talk with KOZO makes you consult Wikipedia more often than an incontinent person rushes to the toilet in one day. The history of KOZO told in one sentence: they absorbed Filter Happier (another great Lebanese band). In reality KOZO is the result of a lot of courage. Andrew Georges (guitar) and Charbel Abou Chakra (bass) were playing in a band doing Sigur Ròs covers at the time. They were looking for a competent drummer to complement the band. Filter Happier on the other hand were a band “in suspension”; their singer had moved to France and their bassist to the USA. Andrew saw Filter Happier play, liked what he saw and mustered up the courage to talk to them (architects are also shy people). Elie el Khoury (drums) quickly agreed to join Andrew’s band and so did eventually Georgy Flouty and Camille Cabbebé (both guitars, and the two non-architects in KOZO). “I was particularly scared to talk to Georgy,” says Andrew during the interview. “He is a pro, he was in bands, he has been on tour in Europe and has this intimidating aura.” (Georgy: “What?”) Architects. Music. Enter Japan. On September 7, 2019, KOZO will launch their debut album “Tokyo Metabolist Syndrome” at the SoundsGood Music Festival in Rayfoun and it’s an unusual album. KOZO may not call it that way but it’s a concept album celebrating metabolism, a post-war Japanese architectural movement, and comparing it to the state of architecture in Lebanon. “Actually, I don’t like the term concept albums,” Andrew says. “it reminds me of herbal, cheesy records from the 1970s.” Charbel and Andrew are both architecture buffs who post regularly about their passion on Facebook. For the rest of us it’s time for a crash course in metabolism. Metabolism was a movement that explored methods of large-scale reconstruction for Japan’s cities severely damaged by the war. Between the 1950s and 1970s, Metabolists like Fumihiko Maki, Kenzo Tange and Kisho Kurokawa emphasized the need for Japanese architects to emulate organic systems in their designs for urban megastructures, highlighting how metabolisms in complex organisms work to maintain living cells (I told you that KOZO were a smart band). In short, buildings and structures (and interestingly enough KOZO means structure in Japanese language) were seen as living bodies consisting of self-sustaining and self-adapting modules. Now how does the music of KOZO relate to the architecture of metabolism? “I tell you how it started,” says Elie. “We started covering songs from bands we liked and from that we figured out our own sound. It was and still is an entire process.” Andrew jumps in: “the idea of architecture in music is about sticking to a process. And accepting the little inconsistencies that happen when you stick to a process. You get those random results at times. We abuse these and make them part of our music.." The music of KOZO is heavy on drums, bass and guitars and their songs often don’t fit the usual radio format. They take their time exploring the landscapes and horizons that lie ahead of them. In exemplary math rock tradition it is music made by nerds that doesn’t sound too nerdy after all. “I like when things don’t sound like you expect them to,” Andrew explains. “With KOZO, it’s my doom metal guitar versus their (Camille’s and Georgy’s) sparkly dream pop riffs. And it works!” Performing the music live feels very physical, Elie adds. “For all of us it is a mental exercise because we use a lot of odd time signatures.” The band admits that they tend to overthink their music when in the studio. “But when we play it live,” says Elie, “that’s when I feel that we really unleash.” “There is a lot of freedom when playing with KOZO. I am not restricted to anything."

Many bands play songs with a “verse - chorus - verse - chorus” schema. KOZO aim to break this established pattern in order to maneuver out of their comfort zone. However there is a side effect: with a regular song you have a place to land on with the song. With songs made by KOZO this comfortable landing spot is gone, for both the band and the listeners. “For me there is a lot of freedom when playing with KOZO,” says Camille. “I am not restricted to anything and I never strum an actual chord. I come in for a bit and then I go out again.”

So how do the listeners react to KOZO’s music? They don’t know when to clap, says Georgy, jokingly. When performing in the north of Lebanon as part of a school event, the kids left the concert but the parents stayed. The band has had great feedback from people whose demographics they didn’t have on their radar. And Camille reveals one of the best kept secrets about KOZO: when they sing (and on many songs they don’t), they sing in Arabic! “For a long time,” Camille tells me, “all my friends thought that we sing in Japanese. Because they looked at the songs titles and assumed that the lyrics would be in Japanese." The song titles are indeed very Japanese and read like a history of the metabolist movement. “Tange” (referring to Kenzo Tange, one of the founders of metabolism), “Osaka 70” (the world exposition in 1970 for which Tange had planned the site), “Capsule Tower” (the icon of metabolism in the Ginza district of Tokyo) and “Tokyo Bay Plan” (Tange’s proposal for extending Tokyo into Tokyo Bay): what is this infatuation that KOZO have with Japan? They have never visited the country and they don’t even speak Japanese (but according to Soundcloud we now have fans in Japan, says Georgy). Andrew takes a deep breath. “As architects,” he explains, “we became enamoured with the concept of metabolist architecture. And then we realized what Japan did after the war and what we did in Lebanon. We sadly ignored whatever potential was present at a certain time and let it slip away. KOZO’s music is about implying our naive understanding of this land - Japan - that is literally far away and dreaming of an architecture for our land that has the same weight as the metabolists had for Japan. People who built futures in the now distant past that we are imagining for our own future, in perhaps the most childish way.” If you have 6:44 minutes to truly understand what Andrew Georges means, then listen to “Tokyo Bay Plan”, the last song on KOZO’s album. If you have only twenty seconds to spare, then fast forward to the end of the same song and focus on Elie firing a final salvo on the drums eight seconds before the end. You will know. That’s Lebanon, that’s the Orient, that’s the land of damnation and salvation, in a musical nutshell. KOZO’s music, although mostly instrumental and without words, is more political than the music of many bands that have been driven to the gallows lately. Lebanese are a people suffering from Stockholm syndrome: they have been conditioned to be in love with their worst enemy, themselves. KOZO are aware of this but don’t know better than to hang in there. “We are a Beirut-based band,” they say, “we couldn’t write our songs outside Beirut.” This was certainly true for the first album. Yalla guys, you now are ready to leave the cocoon. Come to Europe, go to Japan, play concerts, compose new songs, the world is yours. Japanese love surprises. KOZO would definitely be one of them.

1 Comment

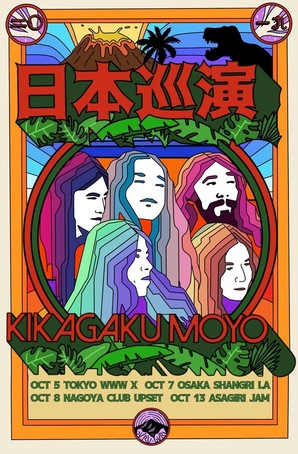

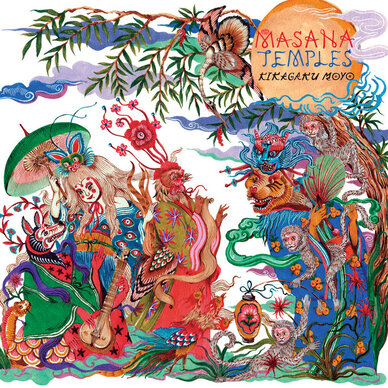

Yesterday evening in Oslo, tonight in Bern, tomorrow afternoon playing at a festival on an alp in the Valais: Kikagaku Moyo don’t take it easy to bring their music to the people. "Last night we did not sleep at all," Go Kurosawa tells me before the concert at ISC in Bern, Switzerland. “We finished the concert in Oslo at 2am, at 4am we were back at the hotel and two hours later we had to leave for the airport.” "What do you do to ease the stress when touring? Working out?,” I ask Go. "No, I'm the drummer”, he replies, "that's already pretty physical. I relax when I play on stage. And when I'm really tired I tell myself that I’m extremely lucky to be able to do what I love to do." Kikagaku Moyo have been around since 2012 when the band started out busking on the streets of Tokyo. Their last and best album so far, "Masana Temples", is from 2018, recorded and produced in Portugal. Besides Go, the band consists of his brother Ryu on sitar, Tomo Katsurada on guitar and all sorts of percussion instruments, Daoud Popal on guitar and Kotsu Guy on bass. Kikagaku Moyo play psychedelic music: they like to improvise and take their time for long songs. Psychedelic music dates back to a time in the 1960s when artists believed that drugs would make their music sound better. Psychedelic drugs such as LSD led to an increased consciousness among consumers, which then had an effect on the music that was composed and played under the influence of these drugs. On the other hand, this music also had the effect of deepening and expanding the experience of the drugs. It was the classic example of a mutual leverage that was not always understood by outsiders. "Can you play psychedelic music without drugs?”, I ask Go. "I think so”, he replies. "In the past I also took drugs, but not anymore. It's about experimenting with your consciousness. You can achieve the desired state without drugs. Sure, the drugs have played an important role in the history of psychedelic music, but reducing everything to drugs would be too much of a shortcut. Psychedelic is like a philosophy: it's also about the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, it's about literature and also about fashion.” (Kikagaku Moyo are indeed a band with style and undoubtedly look good. GQ recently hyped them as “they might be the best-dressed band of the decade.") "Everything is just music and there is no ‘me’ anymore.” The desired mental state, however, can not be reached through two-minute songs. The true trip only begins when the music draws longer. Kikagaku Moyo then try to focus five individuals on one thing, to create something unique under this burning glass. This is a kind of collective meditation and as if in a trance the band shoves forward with their music. "For me as a drummer, this condition is relatively easy to achieve," says Go. "I'm sitting in the back of the stage, in the dark, and can plunge into my own zone, away from the audience. I stop thinking and my arms and hands work automatically. Everything is just music and there is no ‘me’ anymore.” Right from the start of the concert the audience falls into an "instant trance". A repetitive bass line, strumming guitars, Go who sits at the drums and sings: The tense drowsiness of the band goes well with the sleepwalking spirituality of their music. A few minutes into the first song the heads of the listeners already bob dangerously. Kikagaku Moyo are constantly looking for a unification in sound until a groovy bassline sets in and leads the band out of their self-imposed impasse. For some songs the drums are left aside. Tomo has all sorts of sound gadgets in his repertoire - triangle, gongs, cowbells - and Go tries his hand at the flute. These are special effects almost like in filmmaking. My imagination goes into overdrive as well with Kikagaku Moyo’s brand of music. And this not only in a concert setting but already when I listen to their album. Let’s take "Dripping Sun”, the second song from the Masana Temples album. It starts out as a Sergio-Leone spaghetti western and then quickly merges into a 1970s cop movie (it could also be something by Quentin Tarantino, "Jackie Brown" maybe). Later I see a car chase (or even a helicopter overflight?), just before the songs fades quietly back into suburban Japan, to people who wait for the bus while enjoying the sun (if they had the leisure to do so). The city pop of Tatsuro Yamashita trickles down their ears through their Sony walkmen. However the situation is more serious than one thinks. The guitars are racing in California and the last dolphins are dancing far out in the sea. At the end of “Dripping Sun” we are back in the police film which is slowly heading towards a showdown. The hero thinks back to Japan one last time. Then the sun goes down for him as well. For once in Bern, Guillaume Hoarau, the star striker of the local football club, is not the favorite player of the masses. Tonight it's Daoud Popal, Kikagaku Moyo’s guitarist. His fuzz guitar keeps cutting deep furrows in the feel-good-field of non-violent music that his colleagues till with a smile. He is assisted by Ryu Kurosawa's sitar. "The sitar is really a special instrument, it could almost replace an entire band," says Go Kurosawa. "There used to be quite a few bands with sitars. But we want the sitar not to sound like Indian kitsch, but modern. That's why we use the sitar like a guitar, with amplifiers and effect pedals. I assume that Greta Thunberg listens to a lot of psychedelic music. If not, she should start to do so, to give her message even more depth. Mindfulness - towards fellow human beings, towards nature, towards oneself - is contemporary. In this sense, psychedelic music is also contemporary. The message of Kikagaku Moyo may be more necessary today than it was then, when this music had its big bang. It goes beyond a mere "Peace and Love". It means, in the truest sense of the Greek origin of psychedelic, to let the soul manifest itself and to develop the potential of the human mind further. Then we will be able to again give little things the appreciation they deserve. This may seem like little. But we have to start somewhere. |

EditorKurt is based in Bern and Beirut is his second home. Always looking for that special angle, he digs deep into people, their stories and creations, with a sweet spot for music. Archives

September 2020

Categories

All

I'd love to discover you. Share your creations here.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed