Menu

|

Maya Aghniadis loves to invent her own language. She comments good news with Bombastic! or Boom! and refers to all kinds of things and activities as “shizzle” (which, for the Cambridge dictionary, is “a more polite word used instead of the word shit”). Some may say this is gibberish and also will declare it gibberish when it comes to Flugen, the name of Maya Aghniadis’ musical project. According to the Urban Dictionary, Flugen (actual spelling Flügen) means everything and nothing. Maya herself said it in an interview with Project Revolver in 2019: Flugen was a word she used a lot when she didn’t know what to say. She has always been better with music than with words.

And then again, Flugen (the expression) is more than anything and everything. It is what you make of it. For some Flugen is synonymous for a relaxed lifestyle, for others it’s basically just going with life and enjoying the hell out of it. Do not get me wrong: that is not to say that Maya Aghniadis hasn’t any serious ambitions for Flugen (the music). That is not to say that Maya is careless and too easy going on herself when creating music. Quite to the contrary. However, for this writer, Poupayee, Flugen’s new album is the first Flugen record that fully matches the musical goals that Maya Aghniadis has set for herself. Poupayee is not anything, but it is everything and it defines a new musical lifestyle called ethno-electro-jazz. Also in music Maya Aghniadis has invented her own language.

Poupayee has to be viewed and consumed as an album, as a whole, and not as a compilation of songs. One thing leads to another, the sequence of the tracks matters - the track you are hearing, the track before and the track afterwards - and the entire experience when listening to Poupayee is bigger than the sum of its single tracks. “Poupayee tells the story of the different states that a mind can go through,” says Maya Aghniadis. “With every step we come closer to surrender and release to all the shapes of truth.” For impatient characters such as myself, listening to Flugen can be a challenge. Maya Aghniadis has a unique way of composing her music in an almost meditation-like fashion, building up momentum and tension very slowly, very delicately, only step by step. Sometimes it feels like lying on the beach in a hammock, smoking a joint and looking out to the calm sea and waiting for the next wave to break at the shore. This can take a while, but just observing the serenity of the sea brings you the ease of mind that you had been yearning for. When the wave finally arrives, it just might be the next tsunami that surprises you once again. You may run from your hammock but you cannot hide from Flugen’s beats. Maya Aghniadis knows that for some listeners her music feels wobbly. Like a dancer on a rope cautiously trying to hold his balance before he sets one foot forward to precariously move ahead. “That’s not wobbly, that’s just the Flugen craziness”, she says, laughing. Maya is different from the rest of us and so is her music. The music of Poupayee is mostly based on synthesizers and piano, at times underlaid with heavy beats that can probably be felt down on ground floor (I live on fourth floor). Add to this an occasional flute that represents the ethno part of the Flugen sound and the clarinet of Pol Seif. The album starts out rather calm and peaceful but by track three and four - Shades of Blues and Different Ways - hints and flavors of a more dangerous world start to emerge. At first, one barely notices them until we arrive at The Lodge (track 6) where our conscious meets the subconscious and Flugen makes us lose ourselves to a repetitive and broken beat. We then realize that Something Wild (track 7) is bound to happen and that the Peak (track 8) is near where will discover our sensual selfs. "Words are not the essence!"

Such a journey to the truth is never easy as Where To? (track 9) demonstrates. Marwan Tohme (of Lebanon’s indie rock band Postcards) adds his ominous guitar to the Flugen sound and makes this track dark and frightening. We are almost inclined to turn around, not daring to stay the course and to break through this heart of darkness. This would have been a grave error because the final track of Flugen’s new album - Surrender & Release - introduces us to a new world where beautiful melodies fill the air and love takes over.

“Words are not the essence,” Maya Aghniadis explains when describing Poupayee, “gibberish sounds such as the title track itself can bring out the truth more than words”. Music and the emotions it is able to evoke and convey is like a foam, filling the empty spaces in our bodies and our minds. Words can never reach where music can. It is said that children and fools always speak the truth. If the truth lies in gibberish words such as Boom!, Flugen and Poupayee, and in the music these words provoke and entail, then I happily admit: I’m a fool! Poupayee is indeed BOMBASTIC. You can listen to Poupayee on all streaming platforms worldwide. Go here.

0 Comments

After 15 seconds into Murur al-Kiram, Kinematik’s new album to be released on February 28, you already know that you are in for something exceptional. There is no way that an album can start with such a strong drum beat and then end up being a weak recording. Starting an album on a drum beat only also means one thing: Kinematik have thought about this album carefully; they know what they are doing and nothing is random. Murur al-Kiram is a real album, not a collection of songs that were “just ready” to be released. Kinematik may not know it, and they may not even care about it, but their album exactly follows the playbook of “how to approach album track order in the digital age”: start strong - tell a story - don’t worry about shuffling. “What is the story of Murur al-Kiram?,” I ask Kinematik when I meet them in Beirut at the beginning of 2020. Anthony Sahyoun, Rudy Ghafari and Akram Hajj all sip beers when talking to me in the basement of Riwaq, one of their usual hangout places. Anthony is the most outspoken member of the band, so he goes first, as often. “Our first album was a compilation of everything that we were able to do at that time,” he says. “The artistic decisions only had to do with our capabilities as musicians. It was like, ok, this is what we can express, this is what we know how to express, so let’s put it on record.” Rudy Ghafari adds his version of how the second album is different from the first one: “You can say that the first album was one big happy accident. Whereas the second album is a series of mini accidents.” Murur al-Kiram is indeed very different from Ala’, Kinematik’s first album. It contains less guitars and more synthesizers and is driven throughout the album by the multifaceted double drumming of Akram Hajj and Teddy Tawil (who is not an official member of Kinematik, but collaborates with Anthony on another exciting project, May Bardé). If I had to come up with an abstract of the underlying story of Murur al-Kiram, it would go like this: Murur al-Kiram starts with an optimistic, powerful beat which could be a metaphor for young boys enjoying a happy youth somewhere in the fresh air of the Lebanese mountains. Soon the drum beats are followed by synthesizer sounds, the musical expression of fantasy landscapes and future universes of which an innocent adolescent in Lebanon can only dream. "Our presence here is like Murur al-Kiram, like en passant. We are here, but they don't care." With “W Kaza”, the ninth song of the album, the Lebanese reality brutally kicks in. The song is pure destruction and exhaustion, like banging your fists in protest against the gate of a palace (or the building of a corrupt government, if we want to stay in the Lebanese context) that will remain closed, however strong you bang. Murur al-Kiram ends with “Roza” - the most “churchy” of our new songs, as Anthony explains - because after all, when everything in Lebanon is said and gone, religion will stay to soothe the ones that have not found their worldly redemption yet. Since October 17, 2019, the Lebanese again try to change their political system and in fact the entire society, having come out in masses to the squares and streets to protest against the ruling class, the corruption and the sectarian system that suffocates the country and its people. The album's title Murur al-Kiram, which can be freely translated as “the privileged are passing by”, is a sarcastic reference to how Kinematik feel about their situation as Lebanese citizens (and this even before the thawra, as the album was recorded prior to October 2019). Like many other Lebanese, the members of Kinematik sense that their presence in the country is not validated in any way. “It’s like a what-the-fuck-am-I-doing-here kind of thing,” says Anthony. “Our vote, our life has no value. We are stuck with the status quo, our presence here is like Murur al-Kiram, like en passant. We are here, but they don’t care.” “When you listen to W Kaza,” says Rudy, “then remember all your visits to Beirut. That’s the track that expresses most how we feel about everything.” Anthony agrees. “Track nine is literal exhaustion, that’s what it is. It’s exhaustion and defeat and it comes from the drumming. In this song we have this really heavy drum sound and this really heavy bass line. In the studio Akram was slowing down because he got exhausted playing it. And your impulse as a musician would be to pick up the tempo again. But we said no, don’t pick it up. Just get exhausted and let it slow down all the way.” Slow down until all your black thoughts have vanished. What happened to Lebanese band Mashrou’ Leila last year was a big shock for Kinematik. (Mashrou’ Leila were banned from playing at the Byblos festival in Lebanon in 2019. They became the victims of a political power game that was played out on the band’s back, with people leading an online campaign against them because of one or two lines within their lyrics that made references to religion. Of course the fact that Mashrou’ Leila’s lead singer is gay didn’t help their cause either.) “When we last met,” I tell the band, “we talked about your black thoughts. Your ideas about a lot of things are blacker than Mashrou’ Leila’s, but people don’t realize it because your songs have no words.” “Actually my mother said this to me when the Mashrou’ Leila thing happened,” Rudy says. “I was arguing with my mother. She told me, Rudy, your music is actually worse (than Mashrou’ Leila). When Mashrou’ Leila use a reference from the bible, people go crazy. Put words to your music and people would be very pissed off. It’s way worse.” So far Kinematik haven’t put words to their music, because it never felt organic and natural. “If we did,” says Akram, “I think that I would like to say something very melancholic and sad.” “True. there is sadness in our music,” Rudy comments. “But actually, and put the music aside, we are happy people. Despite the depressions we go through. And despite the anger.” Yes, the general tone of Murur al-Kiram is melancholic, however the album is not as gloomy as it might seem when reading these lines. There is also much beauty and hope in Kinematik's music. At the end of the day, Anthony, Rudy and Akram want to stay in Lebanon, they don't intend to leave the country as many Lebanese do. When Lebanese sound defeatist in their talk, it's often meant to be funny, not depressing. To make an album great, it’s not only the music that counts, but also the pauses and the transitions between the different parts of the recording. Judging by this, Kinematik have done an outstanding job with Murur al-Kiram. As Anthony keeps repeating during the interview: the band tried to be as honest and as hard on themselves as they possibly could when recording the album. The material was reworked and reworked until it felt right. There weren’t any hacks and cheap tricks allowed this time around. The composing of Murur al-Kiram was like “you have an idea, you try to abuse the idea,” Anthony explains. “And if the idea survives all of your abuses, then it was a good idea and you keep it.” The result is Murur al-Kiram. It is an album full of ideas that have survived. It is an album made by people who have survived. It is an album that won’t just pass by unnoticed. photos and cover art by Joe Saade An architect walks into a bar… That’s how I intended to begin this article. But searching the internet for jokes starting with this phrase didn’t yield any satisfying results. Certainly not funny ones. Are architects too busy to go to bars? Or are they not funny? For my part I had much fun talking to the musicians of KOZO at Beirut’s Tunefork Studios between rehearsal sessions. And this despite the fact that, or maybe because, three of the five members of the band are architects. KOZO are funny but also very smart people. It may have been my smartest interview ever. A talk with KOZO makes you consult Wikipedia more often than an incontinent person rushes to the toilet in one day. The history of KOZO told in one sentence: they absorbed Filter Happier (another great Lebanese band). In reality KOZO is the result of a lot of courage. Andrew Georges (guitar) and Charbel Abou Chakra (bass) were playing in a band doing Sigur Ròs covers at the time. They were looking for a competent drummer to complement the band. Filter Happier on the other hand were a band “in suspension”; their singer had moved to France and their bassist to the USA. Andrew saw Filter Happier play, liked what he saw and mustered up the courage to talk to them (architects are also shy people). Elie el Khoury (drums) quickly agreed to join Andrew’s band and so did eventually Georgy Flouty and Camille Cabbebé (both guitars, and the two non-architects in KOZO). “I was particularly scared to talk to Georgy,” says Andrew during the interview. “He is a pro, he was in bands, he has been on tour in Europe and has this intimidating aura.” (Georgy: “What?”) Architects. Music. Enter Japan. On September 7, 2019, KOZO will launch their debut album “Tokyo Metabolist Syndrome” at the SoundsGood Music Festival in Rayfoun and it’s an unusual album. KOZO may not call it that way but it’s a concept album celebrating metabolism, a post-war Japanese architectural movement, and comparing it to the state of architecture in Lebanon. “Actually, I don’t like the term concept albums,” Andrew says. “it reminds me of herbal, cheesy records from the 1970s.” Charbel and Andrew are both architecture buffs who post regularly about their passion on Facebook. For the rest of us it’s time for a crash course in metabolism. Metabolism was a movement that explored methods of large-scale reconstruction for Japan’s cities severely damaged by the war. Between the 1950s and 1970s, Metabolists like Fumihiko Maki, Kenzo Tange and Kisho Kurokawa emphasized the need for Japanese architects to emulate organic systems in their designs for urban megastructures, highlighting how metabolisms in complex organisms work to maintain living cells (I told you that KOZO were a smart band). In short, buildings and structures (and interestingly enough KOZO means structure in Japanese language) were seen as living bodies consisting of self-sustaining and self-adapting modules. Now how does the music of KOZO relate to the architecture of metabolism? “I tell you how it started,” says Elie. “We started covering songs from bands we liked and from that we figured out our own sound. It was and still is an entire process.” Andrew jumps in: “the idea of architecture in music is about sticking to a process. And accepting the little inconsistencies that happen when you stick to a process. You get those random results at times. We abuse these and make them part of our music.." The music of KOZO is heavy on drums, bass and guitars and their songs often don’t fit the usual radio format. They take their time exploring the landscapes and horizons that lie ahead of them. In exemplary math rock tradition it is music made by nerds that doesn’t sound too nerdy after all. “I like when things don’t sound like you expect them to,” Andrew explains. “With KOZO, it’s my doom metal guitar versus their (Camille’s and Georgy’s) sparkly dream pop riffs. And it works!” Performing the music live feels very physical, Elie adds. “For all of us it is a mental exercise because we use a lot of odd time signatures.” The band admits that they tend to overthink their music when in the studio. “But when we play it live,” says Elie, “that’s when I feel that we really unleash.” “There is a lot of freedom when playing with KOZO. I am not restricted to anything."

Many bands play songs with a “verse - chorus - verse - chorus” schema. KOZO aim to break this established pattern in order to maneuver out of their comfort zone. However there is a side effect: with a regular song you have a place to land on with the song. With songs made by KOZO this comfortable landing spot is gone, for both the band and the listeners. “For me there is a lot of freedom when playing with KOZO,” says Camille. “I am not restricted to anything and I never strum an actual chord. I come in for a bit and then I go out again.”

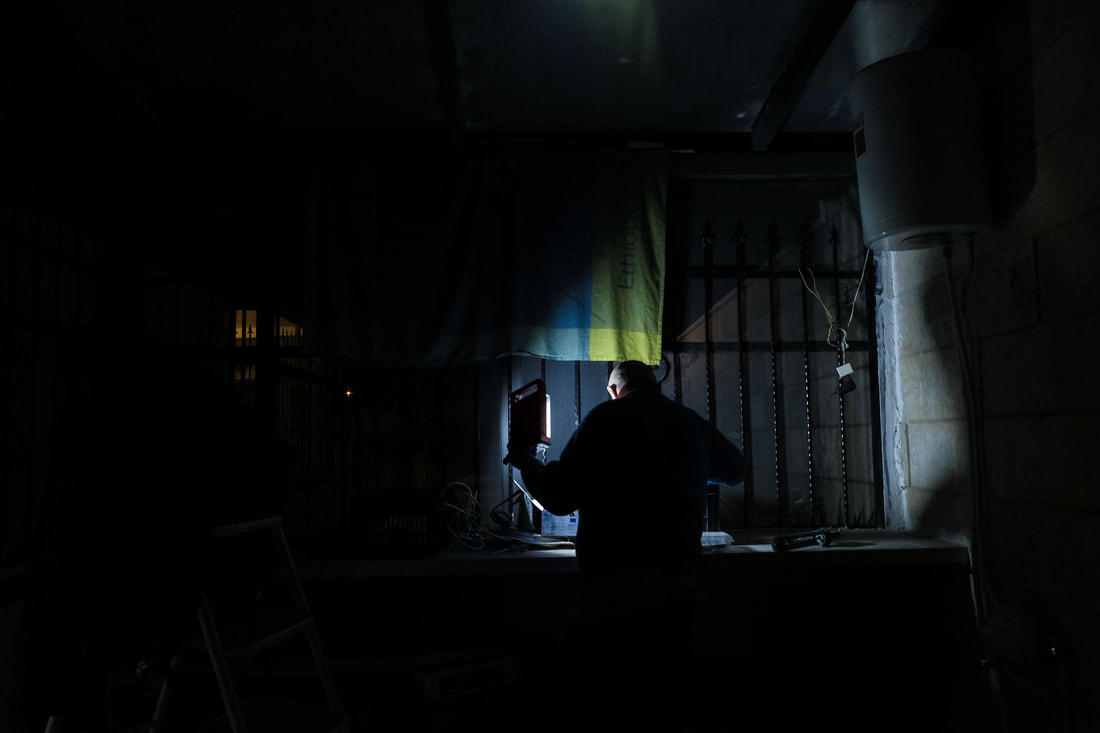

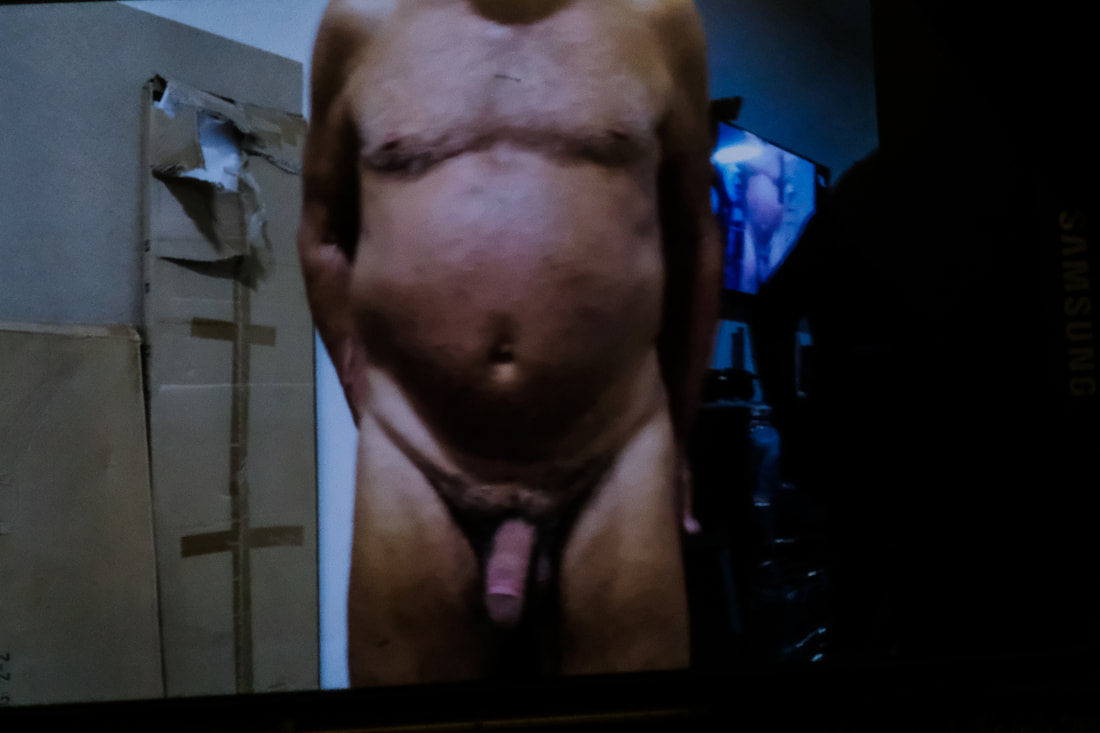

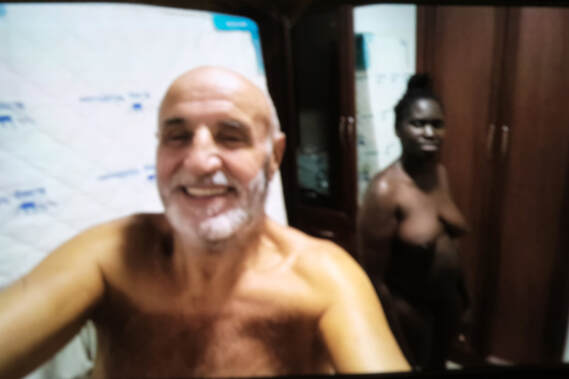

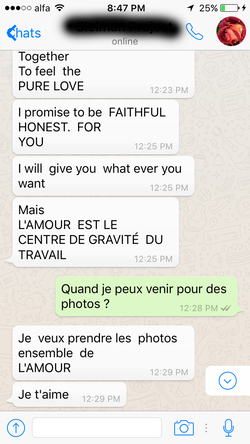

So how do the listeners react to KOZO’s music? They don’t know when to clap, says Georgy, jokingly. When performing in the north of Lebanon as part of a school event, the kids left the concert but the parents stayed. The band has had great feedback from people whose demographics they didn’t have on their radar. And Camille reveals one of the best kept secrets about KOZO: when they sing (and on many songs they don’t), they sing in Arabic! “For a long time,” Camille tells me, “all my friends thought that we sing in Japanese. Because they looked at the songs titles and assumed that the lyrics would be in Japanese." The song titles are indeed very Japanese and read like a history of the metabolist movement. “Tange” (referring to Kenzo Tange, one of the founders of metabolism), “Osaka 70” (the world exposition in 1970 for which Tange had planned the site), “Capsule Tower” (the icon of metabolism in the Ginza district of Tokyo) and “Tokyo Bay Plan” (Tange’s proposal for extending Tokyo into Tokyo Bay): what is this infatuation that KOZO have with Japan? They have never visited the country and they don’t even speak Japanese (but according to Soundcloud we now have fans in Japan, says Georgy). Andrew takes a deep breath. “As architects,” he explains, “we became enamoured with the concept of metabolist architecture. And then we realized what Japan did after the war and what we did in Lebanon. We sadly ignored whatever potential was present at a certain time and let it slip away. KOZO’s music is about implying our naive understanding of this land - Japan - that is literally far away and dreaming of an architecture for our land that has the same weight as the metabolists had for Japan. People who built futures in the now distant past that we are imagining for our own future, in perhaps the most childish way.” If you have 6:44 minutes to truly understand what Andrew Georges means, then listen to “Tokyo Bay Plan”, the last song on KOZO’s album. If you have only twenty seconds to spare, then fast forward to the end of the same song and focus on Elie firing a final salvo on the drums eight seconds before the end. You will know. That’s Lebanon, that’s the Orient, that’s the land of damnation and salvation, in a musical nutshell. KOZO’s music, although mostly instrumental and without words, is more political than the music of many bands that have been driven to the gallows lately. Lebanese are a people suffering from Stockholm syndrome: they have been conditioned to be in love with their worst enemy, themselves. KOZO are aware of this but don’t know better than to hang in there. “We are a Beirut-based band,” they say, “we couldn’t write our songs outside Beirut.” This was certainly true for the first album. Yalla guys, you now are ready to leave the cocoon. Come to Europe, go to Japan, play concerts, compose new songs, the world is yours. Japanese love surprises. KOZO would definitely be one of them. Carmen Yahchouchi is a very courageous person, no doubt. This young photographer from Lebanon is not afraid to take risks when she tries to tell the story that she wants us to know about. When it gets dangerous, Carmen Yahchouchi keeps going, embracing the rush of adrenaline that goes with it. She secretly entered the rooms of sleeping migrant workers when working on a project called Vulnerable Visits. For Beyond Sacrifice, she won the hearts of women who stayed single all of their lives - most of them against their desire. Carmem Yahchouchi shot intimate portraits of proud yet deeply sad women sitting in their bedrooms who were able to exactly analyze when and why their lives’ journeys had taken a turn onto a road they hadn’t planned to follow. Until this point in her career –we are at the end of the year 2016 - Carmen Yahchouchi mostly had taken photos of women and of persons either sleeping or in their bedrooms. Her photos often had two different angles: either her camera looked straight into the eye of the person that she photographed - as in her most famous photo, the intriguing Victoria from the My Mother’s Gun series - or her photos were stolen moments with a voyeuristic feel to it. Carmen Yahchouchi doesn’t deny this side of hers at all. “I love voyeurism!,” she says when I interview her in Beirut. “I always have. I took many photos of my entire family, and of my ex boyfriends too, being a voyeur. Often I caught them while they slept or in other intimate moments.”  When a voyeur and adrenaline junkie meets a narcissistic, attention seeking exhibitionist, things get interesting. When Carmen Yahchouchi meets Suleiman for the first time, she instantly feels that she comes across a somewhat dangerous and perverse man. King Soleil Man, as he likes to be called, had repeatedly posted naked photos of himself on Facebook, sometimes together with African women. Facebook shut down his page as soon as they became aware of it, however Suleiman kept reopening it, posting more photos. Originally Carmen Yahchouchi had looked for single men to complement the many women of Beyond Sacrifice. She soon learned that Suleiman, an 80+ senior from the coast of Lebanon, actually was married with children (although neither his wife nor his children talked to him anymore). “I will tell you everything,” he said to Carmen, “I have nothing to hide.” Suleiman didn’t qualify for the project, Carmen Yahchouchi knew that, but he fit the crispy, out of the box profiles that she likes to get involved with. The exhibitionist had shown his potential and the voyeur had taken the bait. When Carmen visits Suleiman in his house for the first time, she meets two African women there, Sandrine and Rosy. They are migrant domestic workers. Sandrine, from Cameroon, is a warm-hearted and open person and very soon Carmen starts taking pictures not only of Suleiman but also of her. “When Sandrine was there,” Carmen tells me during the interview, “there were no limits. Suleiman and her were in love.” Suleiman opens up to Carmen right from the start. He loves to have her and her camera around and poses naked almost immediately, with no shame at all. Quickly the situation at Suleiman's home deteriorates. Sandrine is arrested in a night club without her residency papers on her and must quit Lebanon on short notice. She leaves Rosy behind, alone with Suleiman. Rosy has a different character than Sandrine: she is calm, shy and very religious. Suleiman had picked her up from the street a few months earlier where she had stranded because of problems with her former employer. And then one day, Carmen receives photos from Suleiman on her WhatsApp, photos that Suleiman had taken, showing him having sex with Rosy. The fate of migrant domestic workers in Lebanon is a very difficult one. Lebanon is home to over 250’000 (female) workers who come from African and Asian countries and work in private households. Stories about them being exploited and abused are widespread. A report published by Amnesty International in April of 2019 titled “Their house is my prison” revealed significant and consistent patterns of abuse. Employers force their domestic workers to work extreme working hours, deny them rest days, withhold their pay, severely restrict their freedom of movement and communication and subject the women to verbal and physical abuse, as well as denying them proper health care. All migrant domestic workers, Amnesty International writes in its report, are excluded from the Lebanese Labour Law and are governed instead by the kafala system which ties the legal residency of the worker to the contractual relationship with the employer. If the employment relationship ends, even in cases of abuse, the worker loses regular migration status. The excessive power employers have in this system over their employees and the strong dependency the women have towards their employers are very obvious. Rosy finds out that Suleiman had sent pictures of her making love with her employer to Carmen. She yells at Carmen. She is outraged. Rosy suspects a plot of some sorts where Suleiman and Carmen had conspired against her. The dynamics of a destructive triangle begin to work: Rosy is very angry with Suleiman because he had sent the photos to Carmen and she is very unhappy with Carmen having "accepted" these pictures. Rosy starts to get bossy with Suleiman. He in turn is not happy with Rosy making such a fuss about the pictures. Suleiman's relationship with Carmen starts to go frosty too. Whereas Suleiman was very open in the beginning, allowing Carmen to take very intimate photos of himself, he now backs up, “starts to go crazy on me” (as Carmen tells me), insults her and even tries to break her camera. Did Suleiman already regret to have agreed to this project? Had Carmen entered his life and his mind more than he was comfortable with? Are we correct in saying that Suleiman is an exhibitionist? Is that his pathological condition? This writer is not a psychologist to answers these questions competently and we shouldn't jump to easy conclusions either. Certainly Suleiman has exhibitionist traits, like we all have - think the many selfies on Instagram and Facebook. Exhibitionism, and the addiction to exhibitionism, is similar to any other substance addiction. Often exhibitionism starts with emotional wounds; it becomes a way to numb the pain from these wounds and a substitute for real intimacy and connection - something the addict both longs for and fears. For adolescents, who are about to discover their bodies and their sexuality, staging and photographing themselves how they like themselves to be seen - and posting it online - strenghtens their self-confidence. It is a well documented behavior which leads us to the follow-up question of what is the level of self-confidence of elderly persons such as Suleiman who experience their bodies slowly “expiring”? Some other things that Carmen Yahchouchi knows about Suleiman at this point of the story: he has a lot (really, a lot, she says) of images on his phone. All photos are from black women, all different women. He is mad about black women. He stays 24/7 on his phone, constantly sending out virtual hearts and flowers. Also to Carmen. With time, Rosy understands that Carmen Yahchouchi is a friend, not an enemy. After all, Carmen is an African woman too. She was born in Bamako, Mali, and lived there until the age of 18. Rosy entrusts herself to Carmen and tells her that she is mistreated by Suleiman. Carmen goes out to buy a suitcase for Rosy so she can pack up her things and leave. Suleiman is furious. Carmen starts to become an actor in her photo project, not just an observing by-stander. She can't remain neutral and choses her side. The line between the art and the reality becomes blurred and actually stops to exist. Does this photo project say more about Carmen Yahchouchi than about her subject, King Soleil Man? What is her motivation to keep visiting Suleiman when he clearly becomes threatening to her? Suleiman sends her WhatsApp messages and writes that he wants to make love with her. One day, while she is with him, he shows her how he googles for “sex Carmen” on the internet. I must be strong now and not show any sign of weakness, Carmen says to herself, when on another day Suleiman starts to caress her neck while sitting next to her on the sofa. “What was this obsession that you had with King Soleil Man, Carmen?,” I ask her when I talk with her in Beirut. “Well, as you know,” she replies, “I like the dangerous and the adrenaline. But with Suleiman it went further. I was not able to get a hold of him. With the women that I had photographed for previous projects, it was easy for me to enter into their hearts. Now with a man… I went mad. I kept telling myself that I must finish what I had started.” To finish what? We all have these father-figures (literally or figuratively), these king-like figures that we put on a pedestal, particularly as a child. Suleiman could easily be one of them, he perfectly fits the profile. And why not put him there? After all, he is a well respected person in his community, a bit strange maybe, but not far off the mainstream. And then at a certain point in our lives we search to demystify these imposing figures and we want to throw them off their pedestals. They have done things that we know of and they know that we know. For a long time we were not able to talk about it, but now we are. However something holds us back. It’s not the right moment maybe, it’s not the right occasion to really turn a desire into action. What are the benefits, what do we have to lose? So we may take aim at another person instead because someone has to fall. You are no king, King Soleil Man. My lenses can see through you. You have become transparent to me. Some of Carmen Yahchouchi's photos may feel uncomfortable to look at. They take us out of our comfort zone. We may think that these photos go too far, that the photographer didn’t stop where she should have. Did Carmen Yahchouchi overly intrude in Suleiman’s private life, can she even be qualified as a stalker? But then again, it was him who invited her into his bedroom, it was him who sent very explicit photos to Carmen. Let me introduce you to one of these “to the point” German words, Fremdschämen. The concept of Fremdschämen means that we are embarrassed because someone else has embarrassed himself (and doesn’t notice, or - even more vexing maybe - doesn't care). Usually we try to avoid this kind of situations, we look the other way, we turn the TV off. Only to turn it on again, to zap until we have found another “The Bachelor”, another “I’m a celebrity get me out of here”, or any other TV show that makes us feel better about ourselves, because these shows provide us with so much material to feel embarrassed about other people. We love to see other people fail. If we feel awkward, even embarrassed by Carmen Yahchouchi's photos, her project was a success.  Carmen Yahchouchi’s photos of the self appointed King Soleil Man also teach us another important lesson: the more we see the less we know. It is not by watching pornography that we learn about the joy of sexual love. It is not by booking a “see all” holiday package to China that we will know more about the inner workings of a society governed by an authoritarian regime. It is not by following Kendall or Kylie Jenner’s Instagram feed that we understand the true personalities of these model-entrepreneurs. Suleiman showing off his erection shouldn’t make us look past his many personal conflicts, his weaknesses, his anxieties. What we see is what he wants us to see. The message he tries to convey is the mirror he would like to see himself in. When Suleiman says “I will show you all I have”, he actually means “I will hide everything”. The last photo of the series shows Suleiman sitting on his bed, all dressed up in winter clothes, confused and lost. His encounter with Carmen Yahchouchi and her camera had made him drop his shield, his facade had disintegrated and his soul was laid bare. Within a few weeks he had gone from close-ups to closed-up. For a long time Suleiman had clung to a distorted image of himself. We all do when it seems to serve us. Because it is too painful to try real intimacy for a change and to finally start healing our emotional injuries. For an even deeper dive into the world of King Soleil Man, here is a selection of additional photos taken by Carmen Yahchouchi. photos by May Arida  “I want to see what will happen if I only do what feels right,” says Frida Chehlaoui - who on stage is simply Frida - to an audience eager to discover this emerging singer/songwriter coming from Lebanon. “I want to see what will happen if I just go ahead and try. And now I see where this attitude got me,” Frida continues, “it got me here to play my first concert in Europe. I am really very happy to be here." The here is Café Marta in Switzerland’s capital of Bern, a cosy cellar made of medieval brick walls in the city’s old town, turned into a café and an occasional concert venue. Frida is accompanied by Marc Rossier on guitar and David Steinacher on percussion, two well known musicians in the Bernese music scene and beyond. Frida had met them just a few days before the concert and two short rehearsals were all it took to make it a well tuned trio. Tonight Café Marta is the hottest place in town: the cellar is crammed with people - and so are the stairs leading down to the cellar and even the steps behind the stage -, it is hot outside and sticky inside and the incessantly revolving fans, despite of all their efforts, cannot make it any cooler. Frida was announced as Arab Soul from Beirut. But what was it exactly that brought such a large crowd to Café Marta on a midweek summer evening? The words Arab, Soul and Beirut all have their own particular connotations, an almost magical promise to discover an emotional territory not usually accessible to Western Europeans. However Frida is much more than what she seems to represent. Starting with a warm and slightly smoky voice, and the natural ability to talk to an unknown audience and make them listen to her, Frida’s universe mainly relies on three pillars: connecting to one’s higher frequency, co-creating and experimenting. All of this is topped by a roof that Frida calls “the role of joy in the creative process”. Why suffer to create when you can walk the path of least resistance and thus bring out the creator that lies in all of us? “I know things beyond the physical realm" As a child Frida signed her first poems as Free-da and thirty something years later this makes more sense than ever. “My connection with the audience is that they see someone on stage who is absolutely free in that moment,” Frida tells me when I interview her after the concert. “I am free to say what I want to say, free to do what I want to do, free to allow myself to feel what I am feeling without thinking if this is going into the right direction.* “What allows you to be this free?,” I ask her. “I know things beyond the physical realm,” Frida replies. Frida’s freedom doesn’t even stop when facing Nina Simone’s Sinnerman, a monument of black American music and one of two cover versions that Frida has in her repertoire. Not happy with the original lyrics (on Judgement Day the frightened Sinnerman goes to the rock, the river and then the sea, desperately looking for protection and finally turns to the Lord who refuses to help him and sends him to the devil instead), Frida added her own twist to the song, because after all the Lord is love and not supposed to send anyone to the devil, no matter how much this person may have sinned. “I see you,” sings Frida in Arabic, “I see the fear in your eyes, I see the chains you’re carrying, but you seem to have forgotten how you were the one who put them there. It is now time for you to see your power, the power of a thousand suns shining from within you, shining to remind you: don’t you know that you and I are one and the same?” This is extremely powerful and beautiful at the same time. Frida’s songs are meant to remind us who we truly are and that we should forget about the restrictions that we limit ourselves with, that we can be much more than we think. In “Out and About”, Frida describes how our bodies must open up to embody the light that we truly are. In “Aala Mahli” (going slowly) Frida tells us the story of the heart that must be our guide, the only guide we ever need. Frida herself is “Bint el Kol” (the daughter of everything); her homage to the divine feminine will also be the title track of Frida’s first album set to be released in September of 2019. Frida is the daughter of the wind, the daughter of the sun and of the waves (“like the waves I can be calm, like them I have been fierce”), she’s the daughter of the earth and the daughter of ether (“unseen and omnipresent, weaving us all into one”). Frida’s concert in Bern was a success beyond expectations. The audience was thirsting for her message of self-love and collective empowerment and for her well tempered dose of spirituality that many of us are lacking in our get-up-and-go lives. Visiting Bern has enabled Frida to meet musicians such as the exceptional accordionist Mario Batkovic and ECM recording artist and bassist Björn Meyer to talk about their approach to music and about possible future collaborations. Already Swiss rapper Greis joined Frida on two songs at Café Marta, subsequently inviting her to be his guest at his own concert later that week. Frida sang Ya Sadi’i (my friend) on this occasion and this song’s story “about the courage to chose the less traveled path to experience the magic unfold so we become the makers of our destinies”, is a story that speaks to all of us, regardless of our mastering the Arabic language or not. Frida’s message is an universal one. We need her to be the companion of our lives for many years to come. from The Open Enso archives. Photos: May Arida  Three concerts in a row in one of the music capitals of the world: that’s why Sandra Arslanian and Sam Wehbi came to London in this early September of 2018. Sandra and Sam are members of Sandmoon, an indie pop/folk and sometimes rock band from Beirut Lebanon. Sandra founded the band eight years ago, a few years after she came back to Lebanon from Belgium where she grew up; she writes all the songs, sings and plays the ukulele, the guitar and the keyboard. Sam plays the lead guitar, particularly when Sandmoon perform live. The rest of the band couldn't make the trip to London, not least because of visa issues. We arrive in a sunny but windy London on Friday afternoon. We: that are yours truly reporter from Switzerland and May, a photographer who is originally from Beirut, like Sandra and Sam. Both of us have known Sandra for quite some time, closely following her career, from releasing three albums and an EP to winning a Lebanese Movie Award in 2017 for composing the score of Philippe Aractingi’s Listen. We meet Sandra and Sam in Katja Rosenberg’s apartment in Walthamstow in northern London. Katja’s flat is small and well stuffed, but this is London where space is rare and expensive. For this weekend the apartment is Sandmoon’s home base. Yesterday’s concert in a chapel was amazing, Sandra gives us the update after we all sit down. Two dozen persons only, but the place was sold out. We played for eighty minutes and the people wouldn’t let us go. Now we are curious what tonight’s concert will bring. It will be a Sofar event at a private place in Bethnal Green. "It is really nice to play in front of people who actually listen to the music." On our way to the Sofar concert Sandra hands out Stimorol chewing gums to everybody. Tonight, Sandra says, I will be the great unknown. Nobody this evening will ever have heard of Sandmoon or Sandra Arslanian. I like the idea. Our music, she explains, might not work in Spain. But in Portugal, with all their Fado, it might. Here in London our music definitely works, people like what we do and how we sound. Are you fed up with Lebanon and the Lebanese audience?, I ask Sandra. Not really, she says. But of course Lebanon is a very small market for English lyrics pop and rock music. And there is another thing: unfortunately in Lebanon only a few people go to see concerts because of the music. They go because others go too and it then becomes a social event. It’s like a herd moving from place to place. It is really nice to play in front of people who actually listen to the music. Sofar tonight takes place at the loft style apartment of Casey and his girlfriend Rachel. Sandmoon start their concert with Home, one of their trademark songs. Sandra sings without microphone, without nothing, to an audience on the floor and on sofas with all eyes on her. Sam is her ideal musical partner, getting the best out of a rusty acoustic guitar that he had to borrow from a friend. With the small combo, Sandmoon depend even more than usual on Sandra’s voice and performance. The audience is like spellbound, particularly when Sandmoon perform The Answer, a song from last year’s recording session in Berlin. Then they play Walk, an old favorite, but not Temptation, a newer song that wails like a prayer. It’s Friday night and the audience asks for something "more party". After the show Sandra is sweaty and exhausted. The public slowly leaves the apartment, they very much liked what they got. We pick up some Chinese food at a takeaway in Walthamstow. Then we all huddle again in Katja’s apartment and eat. "Me improvising on Bach, what the hell!" The next day, when we meet again, Sandra is in a good mood, offering Belgian chocolate to everybody. Sam lies on the bed and fingers around on his electric guitar before he goes into a catchy rock tune from his own Uncle Sam band in Beirut. In the meantime Katja is busy doing some household work, watering plants and hanging laundry. Katja was born in Germany but lives in London since 1998, working as a freelance powerpoint guru and an organizer of art events. It is thanks to her that Sandmoon play three concerts in London. Katja sits down at her piano, jammed between the bed and the wall, and plays Bach. Sam plays along on the guitar, still on the bed, his eyes staring at the ceiling. Me improvising on Bach, Sam says afterwards, what the hell! Saturday night’s venue is the Hornbeam Café, an organic, authentic neighborhood café and also a community center. The Hornbeam is a place similar to the Onomatopoeia in Beirut where Sandmoon like to play. What is Sandra for you?, I ask Sam outside the café, just before the show. Sandra is like a mother to me, Sam says. She is a great teacher; it’s three years now that I am playing with her. She makes me control myself better, musically and also in general. I am still relatively young, Sam explains, and therefore I have a tendency for wanting to storm the sky. Even without the full band, Sandmoon cover a lot of musical ground with their performance this evening. Sandra clearly has made the transition from recording artist to performing artist. She is at ease on stage, displays a lot of self confidence and is closer to the audience than I had ever seen her. During Sandmoon’s concert all their videos are projected in an endless loop on a screen behind Sandra and Sam. The audience sees images of Beirut in the 1960s and of people protesting the political order in recent years. The video of Sandmoon’s 2017 single Shiny Star passes by and Pierre Geagea dances in Beirut Mansion to the music of Time Has Yet To Come. Seeing it like this, from A to Z in one sequence, it is an impressive body of work. On our way back to the apartment we stop for a late night dinner at Thainese, an Asian restaurant on Walthamstow’s main road. We talk about Prince and Bowie, Sandra’s musical heroes, and also about Fentanyl and discuss if pain killers should be classified and treated as drugs. For Sunday lunch we again go to Walthamstow’s pedestrian area and to a Bulgarian steakhouse. What is the way ahead for Sandmoon?, I ask Sandra. Could hiring local musicians in London be possible, to play future concerts here with a full band? It could, Sandra replies. However it is hard for me to play with strangers. Sam and me for instance, that’s like an osmosis. In addition to not being strangers, Lebanese musicians are all shaped by the same experience: Lebanon. Could musicians from London emulate this experience? Often this is an experience of war and it is also reflected in Sandmoon’s current setlist going from songs off the first album raW to Masters of War, a Bob Dylan cover. I don’t know the war that well myself, Sandra says, at least not first hand. In 2006 I was abroad and when my family left Lebanon because of the civil war, I was only seven months old. Does it matter? Despite not personally being there, war and the consequences of it are profoundly anchored in Sandra’s DNA. Back in Switzerland Sandra messages me that Sandmoon will soon start to record new songs, with an aim to have a new album out in 2019. Sandra has been very creative lately, also inspired by the good experience she had playing in London. She was in a flow and has written many songs that now need to be developed, refined and recorded. And: We clearly aim for an another Sandmoon visit to London soon, Sandra says. Londoners dig the melancholic side of Sandmoon’s music and they always love a good storyteller. And that’s precisely why Sandmoon came to London: to find a new audience and new opportunities to spread their message and their musical love. Sandmoon will be back in London; new concerts are scheduled for August of 2019. As for the new album: all the songs have been written - it will be somewhat of a new direction for Sandmoon - two songs have already been recorded and "Fiery Observation", the first video off the forthcoming album "Put a Gun/Commotion", has just come online. For Sandmoon, it's a road that never ends. |

EditorKurt is based in Bern and Beirut is his second home. Always looking for that special angle, he digs deep into people, their stories and creations, with a sweet spot for music. Archives

September 2020

Categories

All

I'd love to discover you. Share your creations here.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed